My Record-Keeping Setup

contents

March 25, 2000

Paris

Hugh printed out my French medical story. I don’t like the way the pages look, but I suppose I’ll get used to them, just as I’m adapting to the laptop he bought me. It’s so different. On a typewriter, when you run out of things to say you get up and clean the bathtub. On a computer you scroll down your list of fonts or make little boxes. It scares me to say it, but I think I’m going to miss my laptop while I’m away. Suddenly I can see what everyone’s been talking about for the past fifteen years.

— David Sedaris, Theft by Finding: Diaries 1977-2002 (2017)

But I am very poorly today and very stupid and hate everybody and everything. One lives only to make blunders.— I am going to write a little Book for Murray on orchids & today I hate them worse than everything…

— Charles Darwin, letter to Charles Lyell dated October 1, 1861

To me, the term record-keeping calls to mind dusty Bankers boxes with looping, slanty years scrawled in sharpie on the side lining the basement hallway. As a kid, empty Bankers boxes were a lot of fun. For my parents, I doubt that dutifully stuffing them with boring ol’ 1093-UGH-es, 2098-BS-es, and itemized accountings of every VHS tape we took to Goodwill was as exciting.

Figure 1. A comparison of my parent’s boring Bankers boxes (A) and my rad Bankers box (B). Note the glow-in-the-dark and holographic elements of B.

Now that I’m all grown up, though, I’ve stepped into my own record-keeping activities. I’m not talking receipts and tax forms: I’m responsible for documenting my computational experiments and work outputs, I benefit from jotting down new ideas from talks and papers, and I’ve taken up hobbies that generate a steady stream of digital artifacts to tuck away. I’m not ready to give up the holographic stickers, pipe cleaners, and glitter glue, though. In my own record-keeping, I want to hang on to at least some of the fun I used to have with Bankers boxes. (Mild obsessive tendencies probably make fun with record-keeping a little easier to come by.)

I’ve come to believe that the tool (and, closely related, the process) I use to keep records is the best way to get the most from my efforts — more than just record-keeping compliance:

- the ability to easily access the record long into the future,

- the eradication of pain points from the record-making process, and

- the infusion of extra value to the act of record-making.

Point 1 is straightforward. Obviously, it’s best not to get caught with your pants down when the IRS comes a-knocking because the Bankers boxes in your basement took a dive below the local water table. There’s a little more here, though. How likely are you to, say, check to see if your Land Before Time I - XIV VHS tapes are actually gone or just missing if 1998’s box is situated deep inside your shrine to Title 26 of the United States Code, under 2002 and behind 1999? What if you stored your records on microfiche and then traded your home Recordak Film Reader away for a Discman? You’re more likely to actually make use of your records if figuring how your Beanie Babies have appreciated against their purchase price isn’t more trouble than its worth.

Point 2 is also straightforward. Most people don’t like pain. Again, though, there’s a little more here. If creating and storing your records doesn’t make you want to rip out your frosted tips, you’ll be more likely to put down your Bop It actually do it. A slick, convenient, maybe even enjoyable record-keeping process makes it more likely that the Thing That Really Matters will be in your Bankers box when the time comes.

Finally, we arrive at Point 3. This one is more subtle. My argument here is that stuffing your Bankers box doesn’t have to be just about covering your bases in case of an audit or a missing furby — “honey, you’re sure we didn’t donate it?” (Hint: jump in your car and just keep driving; it’s coming for you.) I’m arguing that the act of making and storing records be valuable even if you never go through them later. Making and storing records can provide an opportunity for reflection and planning.

Take the process of preparing and publishing academic papers. Once complete, these papers serve a valuable record for other scholars, funding agencies, and even the authors themselves. Aside from all that, however, putting together a paper forces distillation of ideas and compilation and formal interpretation of evidence. Authorship helps authors better understand their own work and tends to break work on really big, really hard problems into more manageable pieces. Often, part of writing a paper is identifying areas for future work.

Influence on behavior and outlook through record-keeping extends far beyond academic authorship. Maybe your annual performance review makes you feel good about yourself for a few days. Maybe filling page after page of your fuzzy lock-and-key diary with transcripts of telephone calls with your friends, and his friends, and his parents, and sometimes even him makes you realize: he’s just not that into you. Maybe writing down what you did last week reveals how many hours of The Office you blitzed through. The answer may surprise you…

In case you didn’t catch on yet, the topic for today is record-keeping. I’ll lecture a little more on my pertinent Thoughts Philosophies & Reckonings plus the experiences from which these capital-letter pomposities originate. Mostly, though, this piece amounts to an extended advertisement for my record-keeping system templ. Because I use this same system to keep a scientific notebook and keep a personal journal, this piece — perhaps jarringly — delves into both topics.

¯\_(ツ)_/¯

Buyer beware.

🔗 Why Keep a Journal

If you haven’t yet, go listen to David Sedaris’ Santaland Diaries. Go. I’ll wait.

June of last year, I got my hands on a copy of Sedaris’ Theft by Finding. This volume presents an (edited) glimpse of Sedaris’ diaries. Many entries are just a few sentences.

May 17, 1979

Raleigh

Gas in four states is now selling for over $1 a gallon. I’d love to work in a service station so I could hear people complain. Apartment life is good. I’m using my ironing board as a kitchen table.

October 9, 1986

Chicago

On the radio, someone was talking about cranes. The ones he’d studied had been taken from their mother at birth. At first they were raised by hand puppets, then later by men who were dressed like cranes. How does a man dress like a crane? I wondered. And are birds really dumb enough to fall for it?

I read all 528 pages in a matter of days. I was struck by how compelling Sedaris’ stream of detached, succinct moments felt when each was presented for its own sake. Since plowing through Theft by Finding, I’ve enjoyed tucking away vignettes of my own. It feels like netting butterflies and pinning them in a display case. When you start to look, they’re all over. I overheard this in the lobby of BPS.

My cat keeps singing off his whiskers because he tries to lick the candle. Half of his eyebrow whiskers and his face whiskers are gone. He’s very lopsided.

For me, these little moments have become the glow-in-the-dark stars and holographic stickers on the side of my Bankers box. They make me want to get in and play. The small satisfaction I get from arranging my collection and my continual encounters with new specimens are most of why I have stuck with record-keeping at all.

Surprisingly, some of my collection have come in handy later. I populated my recent reflective writing on education and outreach primarily with anecdotes drawn from snippets of conversation I had tucked away contemporaneously.

The most valuable return on my investment in journaling is greater confidence and comfort writing. When I sit down to put a few days’ worth of material in my journal, I confront a series of decisions. Why is this interesting? What details must I leave in? What can I take out? Are my own thoughts or reaction relevant? In what order should I reveal information? To what pieces of information should I lend special emphasis? With these decisions made, writing becomes a matter of devising and arranging a few clauses to meet design specifications.

Working within this objective-oriented framework — as opposed to aiming to write “well” — is much simpler and more satisfying. When I started my journal, I produced play-by-play prose that weighted in at several paragraphs. Today, I’m mostly down to a few sentences at a time. I hope this practice making every word tell will transfer to my scientific writing. Everyone can use a leg up in competition for funding and publication.

🔗 Why Keep a Lab Notebook

My experience with laboratory science outside the classroom is primarily through the USDA Agricultural Research Service (ARS). I worked on-and-off at the Corvallis office as a Biological Science Aide for four years with Dr. Chad Finn’s small fruits breeding program. A lab notebook had no relevance to most of what I did — hoeing, building trellis, picking fruit. Although I’d occasionally prepare media, work in the hood, count seeds, weigh fruit, or figure thorn density, I never kept a lab notebook of my own. Many of my co-workers did, though. As I’ve moved over to the realm of computer science, I’ve noticed that keeping a scientific notebook is not nearly as commonplace as in laboratory sciences.

Before the USDA — as a Model UN kid — I became a connoisseur of obscure government documents. If the document is inexplicably titled in all caps, even better. (Shout out to the HELLENIC REPUBLIC MINISTRY FOR THE ENVIRONMENT, PHYSICAL PLANNING AND PUBLIC WORKS 4th NATIONAL COMMUNICATION TO THE UNITED NATIONS FRAMEWORK CONVENTION ON CLIMATE CHANGE.) In that spirit, let’s get a sense of what laboratory notebooks are useful for according to a 2009 slide deck titled GOOD LABORATORY NOTEBOOK PRACTICES from the good old USDA ARS. I’ve rearranged some of the material to suit this format. That said, what’s the first thing we should know?

ALWAYS USE OFFICIAL ARS Laboratory Notebook (ARS FORM 1)

Okay. Sure. Even if you’re not using ARS FORM 1, why keep a laboratory notebook?

Record of ARS Research

- Records the original intent of a scientific investigation

- Preserves the experimental data and observations for future reference

- Assists future researchers with the understanding/reproduction of your experimental observations

- Valuable resource for writing a paper

- Evidentiary tool (patents, etc.)

Three points here merit elaboration.

- Reproducibility is a core principle of science. To the extent it can help make sure the experiments you report are repeatable (thus, in a sense, valid), a notebook is important.

- In most cases, funding for you (the scientific peon), your equipment, and your work comes from benevolent funding agencies. Maintaining a clear record of what you did, even the bits that didn’t work out, is the right thing to do.

- Is there anything quite as satisfying as copy-pasting over a nice long paragraph from your notes into your manuscript? No, there isn’t. As the ARS slide deck firmly exhorts,

A WELL WRITTEN NOTEBOOK SAVES TIME

I’m sold. The laboratory notebook seems like a useful tool. How, pray tell, should we keep ours?

A. OFFICIAL ARS NOTEBOOK GUIDELINES

- Use as a Daily Log for research work plans and results

- Copious descriptions with elaborate details are preferable

- Enough detail should be given so that another researcher could repeat your work based on your notebook entries and make the same observations

- Do not use any erasable medium such as a pencil or erasable ink

- Make corrections by crossing through the item and initialing

- If the error is more than a few words, an explanation of the error should be noted in the margin where the error is corrected

- Do not remove any pages from the Notebook

- Cross reference instrument printouts when such data is retained in a separate location

- Date entry and initial each filled page

Anything else we should know?

UNNECESSARY DEROGATORY COMMENTS should not be made in the Notebook as results may be valuable in a different way than anticipated

I try to refrain from unnecessary derogatory comments on my bank statements in case I’m wealthy in a different way than anticipated, too. Nonetheless, it won’t hurt to keep this in mind the next time I’m very poorly, very stupid, and hate everybody and everything.

🔗 Design Requirements

Now, with all this in mind, we get to the fun part — describing what requirements an ideal record-keeping tool should meet. I’ll also describe some of design solutions these requirements bring to mind.

-

I want to store text with some simple formatting, charts/figures, and maybe some digital drawings. Markdown and PDF should cover my bases here.

-

If I really want to store some other type of digital asset, I should be able to. If my system just keeps files in a really simple local directory structure, I can stash away whatever I want.

-

I want to write in my favorite text editor with my own favorite key bindings, color scheme, and other bells and whistles. In the words of a wise woman in expensive sweatpants I saw in a television advertisement,

Why would you put on clothes if you can shop in your comfy pants?

Enough said.

-

Right now, my Atom is my comfy pants. When I jump ship for the Next Trendy Text Editor, though, I want to change nothing in my record-keeping tool. In other words, I don’t want to build my tool on top of Atom or explicitly interface my tool with Atom.

-

I want to use my record-keeping tool through a command line interface on Unix machines. Again,

Why would you put on clothes if you can shop in your comfy pants?

Cross-platform compatibility with Windows is not a priority.

-

I want to prevent accidental post-hoc modification and strongly encourage proper documentation for intentional post-hoc modification. Let’s revisit some of the admonitions from our friends at the ARS.

- Do not use any erasable medium such as a pencil or erasable ink

- Make corrections by crossing through the item and initialing

- If the error is more than a few words, an explanation of the error should be noted in the margin where the error is corrected

- Do not remove any pages from the Notebook

You know what this sounds a lot like to me? Version control. By version control, of course, I mean Git.

Even with version control, can you still obfuscate post-hoc modifications to your records if your really put your mind to it? Certainly. At least you won’t accidentally make modifications after the fact or absentmindedly fail to document them.

-

I don’t want to lose my records after I store them.

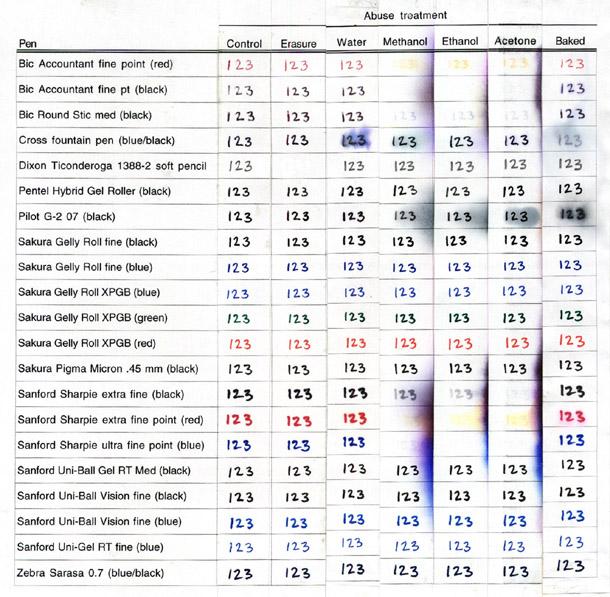

Figure 2. Results of methanol soaking on paper records, taken from GOOD LABORATORY NOTEBOOK PRACTICES (2009) from the USDA ARS.

Unless proper care is taken, digital records can be as fragile as paper records. Like paper records, they can suffer physical damage. (If I’m spilling high-proof alcohol on my work laptop, however, bigger problems than damaged records are afoot.) The obvious solution here is to keep a copy in the cloud where smarter and more careful people will take care of your data for you. If we’re already working with Git, keeping a remote repository up on GitHub would be the obvious way to accomplish this.

More insidiously, if your digital content is stored using a proprietary file format or database system, you’re relying on continuing support from the proprietors. When I worked at the University of Puget Sound chemistry storeroom, we had great time wrangling vintage AppleWorks documents (stored on a prodigious collection of floppy disks, no less). You’re much better off with open source formats, but without continuing community support you might potentially still set yourself up for a real pain in the neck.

I don’t want to rely on whatever tool I use to create the records to read them. For me, this means storing assets as Markdown and PDF files in a directory structure (instead of a database). Markdown files, in particular, should be just fine to page through even without an easy way to render Markdown to HTML. If either of these file formats aren’t easy to work with in the future, God help us all.

-

I want certain components of my text entries to be consistent (e.g. entry date, headings for content sections, etc.). I also want my entries to follow a consistent file-naming scheme. I want some of the consistent parts of my to be programmatically determined (e.g. the date). Some consistent parts, I might want to manually determine on a case-by-case basis. Clearly, some sort of templating of entry content and file path will be necessary.

-

I want to sync my content across devices. If we use GitHub, this is trivial.

-

I want to view my PDF records and HTML renderings of my Markdown records in a web browser. If we use Github, this is trivial.

-

Sometimes, I want to compile my Markdown records to PDF or HTML. Rendering local Markdown files to PDF and HTML is easy enough with tools like Pandoc. This can easily be achieved through a separate script or Makefile and doesn’t have to be part of my core tool.

-

I want my solution to be lightweight. I want minimize the initial time investment I put into my record-keeping tool. Also, I want to minimize any ongoing maintenance to my record-keeping tool. I have better things to do.

My first choice, of course, would be someone else’s existing tool. Then, I would get startup and maintenance for basically free. If I must to code my own tool (*dramatic swoon*), I want to use Python and write a proper package. And yae, I was glad when they said unto me,

Why would you put on clothes if you can shop in your comfy pants?

Spoiler: I wrote my own tool. As of version 0.6.1, templ weights in at 197 lines of Python plus some YAML files.

-

I want my tool to be free (like free beer) and open-source. I’m cheap and I want to understand what’s going on.

-

Finally, when I get fed up with whatever tool I’m using or find something better, I want an easy break — I don’t want to be stuck in divorce court when I should be on my honeymoon. Having direct access to my content as Markdown and PDF files in a precise, simple directory structure at least gives me a fighting chance to script my way out of eternal alimony payments.

🔗 Other Tools

For a few years, I dabbled with Day One and Evernote. Intermittently, I used Gmail as a kludgy idea journal. I’ll leave counting up how many of my design requirements these services fulfill as an exercise for the reader. You probably won’t need both hands to keep the tally.

I’m obviously not the first to confront the lack of satisfactory tools for keeping records like a hacker.

As it turns out, I’m not even the first within my own academic pedigree!

After starting out on my own tool, I learned about my labmate Rose’s Noodle Notebook.

It hits many more of my design requirements than anything else I have yet to encounter.

However, her tool takes a slightly different perspective on the record-keeping problem than I do.

It very well might prove a better fit for your design requirements, though.

For your edification, here’s a blurb pasted in from the project’s README.md.

🔗 What is Noodle?

Noodle is a flat-file lab notebook that saves your files as plain html in the location of your choice.

Features:

- Data files are saved as flat HTML

- Rich-Text editor (CKEditor)

- Image uploads and browser

- Background AJAX/JQuery data saving

- Runs locally

- Cross-platform

Requirements:

- Python

- Web Browser with Javascript

🔗 Why does this exist? Why would you ever make this?

Essentially, all lab notebook software out there sucks in various ways. They either use a proprietary, non-text-based file format (Word, Pages), don’t play well with Dropbox (Papers 2), require a database or an service (Evernote), aren’t free (all of the above), or are lacking in useful features, like rich-text formatting (iPython Notebook, Texts.io).

So, I made one that overcomes these shortcomings. The system is based around Python, Flask, Flask-FlatPages, CKEditor, and JQuery. Noodle stores all of your pages as plain html, so you can just open them up natively in your browser, or text editor of choice without needing any other tools. This makes them future proof, which is a BIG DEAL for science. Relatedly, all the files are plain text, so you can use whatever text-based searching or tagging tools/systems you feel like using. Nothing is denied you by the format.

You can find Dr. Canino-Koning’s Noodle Notebook on GitHub. Go check it out.

🔗 templ Usage

Now that we’ve laid out the design requirements for my record-keeping tool (and I’ve built it) we get to the fun part: seeing the tool in action. Basic usage is as follows.

usage: templ [-h] [--full-path] [-m] entry_type

positional arguments:

entry_type entry type (specify which yaml template file to use)

optional arguments:

-h, --help show this help message and exit

--full-path return full path on stdout (instead of relative path)

-m, --manual-fill prevent automatic fill-in of template fields (manually

fill in all fields)

If an entry file does not already exist, an appropriate templated file is initialized.

The path to the entry file is passed to STDOUT, regardless, allowing for fancy Bash tricks.

Open a template-initialized entry file or an existing entry file with your favorite text editor from the command line! For example, if I did this on January 1, 1970

atom $(templ je)

I would open a new atom tab pointed at 1970/1/1-je.md initialized with

## todo

## done

## misc

ready for me to write down my thoughts for the day.

Templates can dynamically populate both the path and the text file generated with content generated automatically or requested from the user. For example, when I was at a seminar on September 29th, 2017, and did this (answering some command line prompts generated by templ)

atom $(templ talk)

speaker-last > Wiser

keyword > conceptions-randomness

talk-title > Student conceptions about randomness and mutation

speaker-first > Michael

location > BEACON Seminar

I got a new atom tab pointed at talk/wiser-conceptions-randomness-2017-09-29.md initialized with

# Student conceptions about randomness and mutation

Michael Wiser

09-29-2017

BEACON Seminar

## synopsis

## misc

ready for me to take notes on all of the crazy things undergraduates think about randomness.

If it’s no longer the 70’s and I want to open that old journal entry, I use the -m flag to manually fill all fields.

Performing

atom $(templ je -m)

cur-year > 1970

cur-month > 1

cur-day > 1

opens a new atom tab pointed at my existing file 1970/1/1-je.md

## todo

* buy bell bottoms

* wear my favorite wide-collar shirt

## done

* fed my pet rock

## misc

Just tryna be stayin' alive tbh.

You can do other cool things with fancy bash tricks. Remove the entry file. Compile the entry file to a PDF with pandoc. Put the entry under version control. Remember, if the templated path already exists, no changes are made to the file living there when templ is called.

rm $(templ pr)

pandoc -o out.pdf $(templ je)

git add $(templ pr)

A complete workflow might look like this.

atom $(templ je)

git add $(templ je)

git commit

git push origin master

When I want to store a PDF file or anything else, I just manually put it into the file tree. For example, if I want to store some hand-written notes I’d just place them in like so,

mv file.pdf journal/2017/09/29-pd.pdf

(A planned enhancement should make this even easier.) Update: now, I just do

mv file.pdf $(templ pd)

Interested in more? Take a look at an example journal made with templ here. Take a look at an example note-taking system made with templ here. The source code and installation instructions for templ are on GitHub.

🔗 templ Implementation

What’s going on behind the scenes? Here’s a high-level sketch:

- templ gets called with the argument

xyzon January 1st, 2018. -

templ looks (within the templ package) for the file

templ/templates/xyz.yaml. Here’s what the filetempl/templates/xyz.yamlmight look like:# a comment about xyz entry template filename: "class/{class-id}/{cur-month:02d}-{cur-day:02d}.md" template: | # my very exciting {city} notes *today's date: {cur-month}-{cur-day}* - templ locates the

filenamefieldtempl/templates/xyz.yaml. - templ runs the raw content of

filename(e.g.xyz/{cur-year:02d}-{cur-month:02d}-{cur-day:02d}-{city}.md) through standard Python string formatting. - For each token in curly braces, (e.g.

{cur-day:02d}where the token iscur-dayand02dinstructs the formatter to paste in a two-digit number) the string formatter performs a dict lookup for the value to plug in. - The dict has been pre-populated with the

token:valuepairs for which thevaluecan be programmatically generated (e.gcur-day:1). - If the token is missing, the user is prompted at the command line to provide it (this is accomplished by overridding the dict’s

__missing__method). - At the prompt

city >the user enterseast_lansing. - The final formatted filename is produced:

xyz/2018-01-01-east_lansing.md. - templ checks to see if the file

xyz/2018-01-01-east_lansing.mdalready exists. - If

xyz/2018-01-01-east_lansing.mdexists, templ prints the filenamexyz/2018-01-01-east_lansing.mdtostdoutand returns. - If

xyz/2018-01-01-east_lansing.mddoesn’t exist, templ applies standard Python string formatting to the raw content of thetemplatefield oftempl/templates/xyz.yaml. - The exact same dict lookup process as before is used to plug in values for tokens in curly braces.

Note that the key-value pair

city:east_lansingis already in our dict so the user isn’t queried for it again. -

The final formatted template string is produced:

# my very exciting east_lansing notes *today's date: 1-1* - The final formatted template string is written to

xyz/2018-01-01-east_lansing.md. - templ prints the filename

xyz/2018-01-01-east_lansing.mdtostdoutand returns.

There you have it. There are just a two more implementation details to note.

- templ is written as a proper Python package. You can have it up and running at your command line in seconds using pip.

- templ is set up so making your own templates is trivial.

Add a new YAML file to

templ/templates/with the fieldsfilenameandtemplate. Then, reinstall using pip (remembering the--upgradeflag).

🔗 Limitations

If you suffer from command line phobia, templ obviously isn’t the right tool. If you’re just unfamiliar and ready to give the command line a try, maybe templ could work for you.

Currently, there’s no really slick way to add inline images using templ. You can do it, though. It’s not even that bad. In the context of a journal built with templ (like this one), this might be achieved as follows.

journal/2018/01/21-je.md:

# My file built by templ on 01-01-2018

Now I'm filling in the content.

I'm using my favorite text editor so I'm happy and stuff.

:) :) :) :) :) :)

Okay, time to put an image in.

Wow, much amaze.

journal/2018/01/21-img/doge.jpg:

Rendered result:

🔗 My file built by templ on 01-01-2018

Now I’m filling in the content. I’m using my favorite text editor so I’m happy and stuff.

:) :) :) :) :) :)

Okay, time to put an image in.

Wow, much amaze.

Two planned enhancements (8, 9) should make the image insertion workflow somewhat less arduous. Update: now, you can streamline the image insertion workflow as follows.

atom $(templ je)

journal/2018/01/21-je.md:

## My file built by templ on 01-01-2018

Now I'm filling in the content.

I'm using my favorite text editor so I'm happy and stuff.

:) :) :) :) :) :)

Okay, time to put an image in.

Bring back up your terminal.

mkdir $(templ jd)

mv doge.jpg $(templ jd)

templ ji

filename > doge.jpg

When you switch back to your open file journal/2018/01/21-je.md, you’ll find it with the following addition.

journal/2018/01/21-je.md:

## My file built by templ on 01-01-2018

Now I'm filling in the content.

I'm using my favorite text editor so I'm happy and stuff.

:) :) :) :) :) :)

Okay, time to put an image in.

Leaving paper notes behind, I can’t shake an occasional annoyance over my inability to flip through physical pages. Often, I find this technique to be more useful than text search for locating a particular passage. Ranger emulates something like digital page-flipping, but it’s still not the same.

🔗 Let’s Chat

I would love to hear your thoughts on journaling like a hacker!!

I started a twitter thread (right below) so we can chat ![]()

![]()

![]()

Wrote a little something on my personal journaling/lab notebook setup 🌟 #doitlikeahacker https://t.co/oGZEyLIlNG pic.twitter.com/vmDvJZ0INj

— Matthew A Moreno (@MorenoMatthewA) January 22, 2018

Pop on there and drop me a line ![]() , make a comment

, make a comment ![]() , or leave your own tips & tricks

, or leave your own tips & tricks ![]()