Advancing Genomes in MABE

🔗 Project Introduction

MABE, or Modular Agent Based Evolution Framework, is a platform which allows users to create populations of digital organisms and analyze the effects of virtually evolving these populations. One of the key components of MABE is the genome class, which represents genomes for digital organisms in the population. The goal of this project is to advance the genome class in MABE by optimizing its memory consumption and runtime.

If you would like to learn more about the MABE framework, take a look at this Introduction to MABE blogpost from my team!

🔗 Genomes in MABE 1.0

In biology, genomes are an organism’s entire set of DNA and allow organisms to maintain themselves and function properly. Similarly, in MABE, the genomes of digital organisms are represented as lists of values which can be read from, written to, and mutated from parent to offspring. Every genome has a contiguous piece of memory to store its values. Genome classes in MABE are written using C++.

🔗 Naive Genome Class Implementation

The naive implementation of the genome class uses a vector of bytes to store its values. As a result, it uses standard library vector functions to perform the mutations.

std::vector<std::byte> sites;

To perform an overwrite mutation which replaces the values starting at position index with the values from the segment vector:

for (size_t i(0); i < segment.size(); i++) {

sites[index + i] = segment[i];

}

To perform an insert mutation which inserts a segment std::vector<std::byte> segment at position index :

sites.insert(sites.begin()+index, segment.begin(), segment.end());

To perform a remove mutation which deletes n sites from position index:

sites.erase(sites.begin()+index, sites.begin() + index + n);

When cloning genomes from generation to generation, the parent genome sites vector is simply copied into the offspring genome’s sites. Mutations are later applied to the offspring.

The naive implementation allows for quick random access because it uses contiguous memory. It may also initially seem like the easier or cleaner solution to implement, since it uses familiar standard library functions.

🔗 Drawbacks of the Naive Implementation

- Genomes are often very large, from hundreds of thousands of sites to millions of sites.

- With large genome sizes and low mutation rates, the number of sites mutated in an offspring is significantly less than the number of sites which remain the same between parent and offspring.

- This makes the naive genome class’s approach of directly copying genomes from parent to offspring very inefficient in terms of time and memory, much like the gif below!

🔗 Change Logging as a Solution

- Change logging’s goal is to eliminate excess copying of genomes from parent to offspring.

- With change logging, genomes will only store the differences between parent and offspring genomes.

- Each genome will keep track of a log of changes, documenting the mutations between the last saved parent genome and the current genome. The parent genome should be reset whenever the changelog becomes too large.

- Using the changelog, the current genome can be reconstructed.

- Any random site in the current genome can also be accessed without having to store a full copy of the current genome.

Theoretically, change logging can save significant time and memory, especially for larger genomes. This project aims to examine how a change logging genome implementation performs compared to the naive genome implementation.

🔗 My Algorithm for Change Logging

🔗 Data Structures:

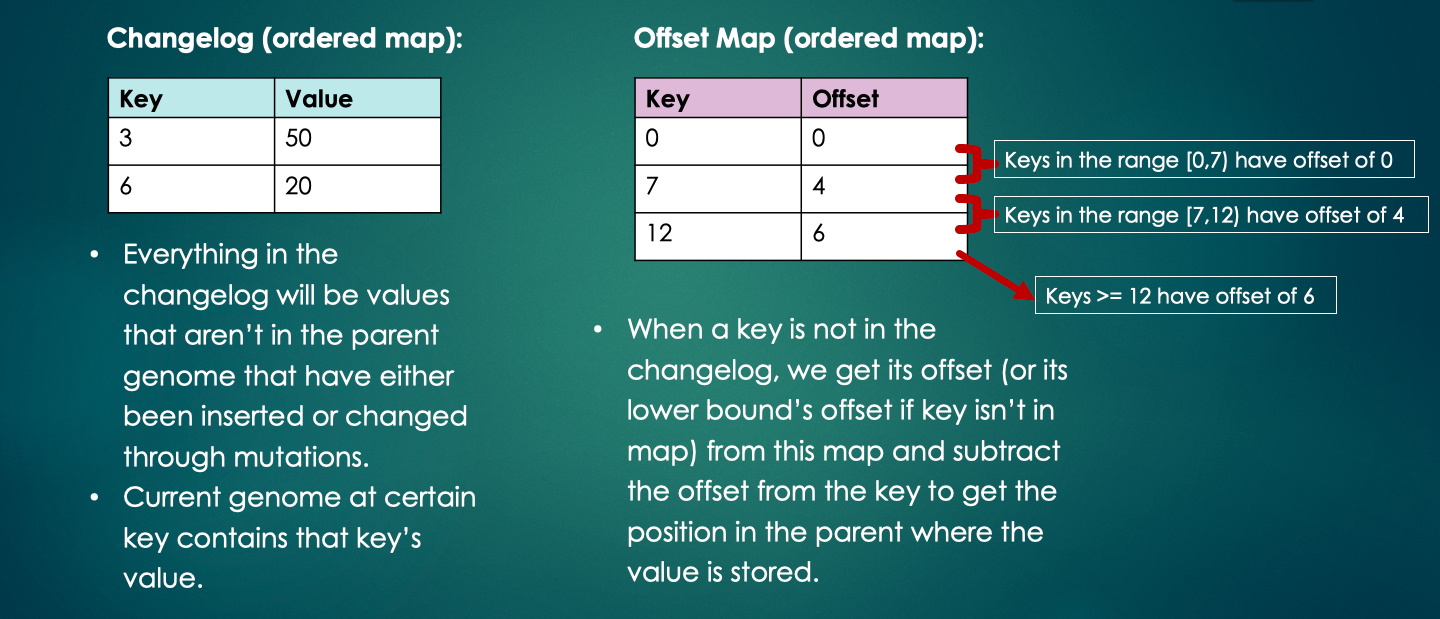

- Each genome stores a changelog and an offset map.

-

Changelog: standard library ordered map

- The key represents the position in the current genome.

- The value represents the value at that position in the current genome.

- Everything in the changelog will be values that aren’t in the parent genome, that have either been inserted or changed in the current genome through mutations.

-

Offset map: standard library ordered map

- We check the offset map for all keys that are not in the changelog.

- The key represents a position in the current genome.

- The value is the offset (how much that position has shifted from the parent genome to the current genome).

- The offset map can be viewed in ranges, where keys between key A and B have the offset of key A (the lower bound).

- When a key x isn’t in the changelog, we find the closest key in the offset map that is less than x and subtract its offset from x to get the position in the parent. We can then access the correct value in the parent.

- The offset map will always begin with a single key-value pair (0,0) to indicate that all positions 0 onward have not been offsetted yet.

-

Changelog: standard library ordered map

🔗 Parent Genome:

- The parent genome is represented as a shared pointer to a vector of bytes. The vector of bytes contains the parent’s values.

std::shared_ptr<std::vector<std::byte>> parent; - When a genome is created from scratch, its shared pointer’s vector is populated. The mutations after this are stored in the changelog and offset map, and the parent is not modified.

-

Cloning a genome creates an offspring for that genome with identical genome values. The offspring is then mutated.

- When an offspring genome is created through cloning, the offspring’s shared pointer is set equal to the parent’s shared pointer.

🔗 Advantages of using a shared pointer:

- A standard library shared pointer in C++ keeps track of a pointer to an object (vector of bytes in this case) and a count of the number of shared pointers pointing to this object. Each shared pointer owns its object, so once the count becomes 0, the shared pointer deletes its object and deallocates the object’s memory. Thus, in this implementation, the shared pointer automatically cleans up any parent which has no offspring pointing at it.

- Resetting the parent shared pointer is more efficient than the naive implementation’s approach of copying over the entire parent vector.

🔗 Insert, Remove, and Overwrite Mutations:

-

Insert mutation: inserts value(s) at a certain position in current genome and changes genome size

- The demo below goes through all of the steps involved in an insertion. To replay, scroll over the gif again.

- The demo below goes through all of the steps involved in an insertion. To replay, scroll over the gif again.

-

Remove mutation: deletes value(s) at a certain position in current genome and changes genome size

- The demo below goes through all of the steps involved in a deletion/remove. To replay, scroll over the gif again.

- The demo below goes through all of the steps involved in a deletion/remove. To replay, scroll over the gif again.

-

Overwrite mutation: change the value of a single or multiple sites in the genome

- The demo below goes through all of the steps involved in an overwrite. To replay, scroll over the gif again.

- The demo below goes through all of the steps involved in an overwrite. To replay, scroll over the gif again.

🔗 Random Access:

-

The

getCurrentGenomeAtfunction below shows how to access position (pos) in the current genome.std::byte getCurrentGenomeAt(int pos) { /* create an iterator for the changelog and check if the changelog contains pos */ std::map<int,std::byte>::iterator changelog_it; changelog_it = changelog.find(pos); if (changelog_it != changelog.end()) { /* changelog does contain pos so just return the value from changelog */ return changelog_it->second; } else { /* changelog does not contain pos so get the value from the parent */ /* create an iterator for the offset map and check if pos is in the offset map */ std::map<int,int>::iterator offsetmap_it; offsetmap_it = offsetMap.find(pos); int pos_offset = 0; // the offset used to index into the parent if (offsetmap_it != offsetMap.end()) { // offset map contains pos, so just get pos' offset pos_offset = offsetmap_it->second; } else { /* offset map doesn't contain pos so must get offset of the closest key less than pos (pos' lower bound) */ std::map<int,int>::iterator lb_it; lb_it = offsetMap.lower_bound(pos); if (lb_it != offsetMap.begin()) --lb_it; pos_offset = lb_it->second; } // get value from parent at index (pos-pos_offset) return parent->at(pos-pos_offset); } - If the requested position is in the changelog, the time complexity of random access is

O(logn), wherenis the number of elements in the changelog. Searching through an ordered map has time complexityO(log(size of map)). So in this case, since we search through the changelog withfind()to check if the requested position is there, the time complexity isO(logn). - If the requested position is not in the changelog, the time complexity is

O(log(mn)), wheremis the number of elements in the offset map andnis the number of elements in the changelog. This is because we first search for the position in the changelog withfind()which islogn. Since it isn’t in the changelog, we also search for the position in the offset map usingfind()which islogm. Therefore,logm+logn = O(log(mn)).

🔗 Results:

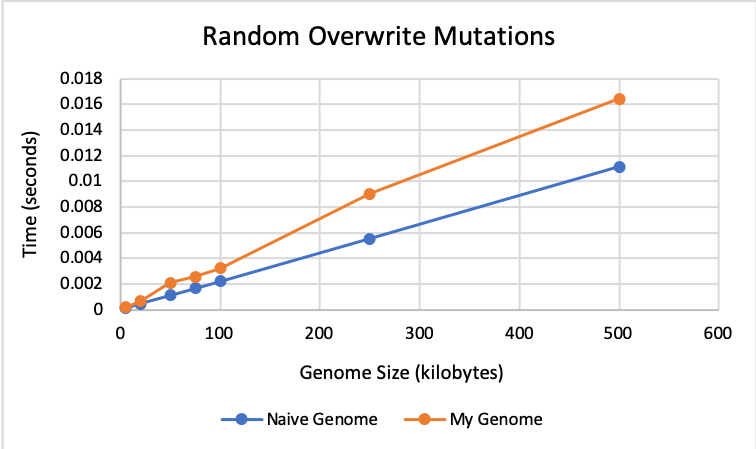

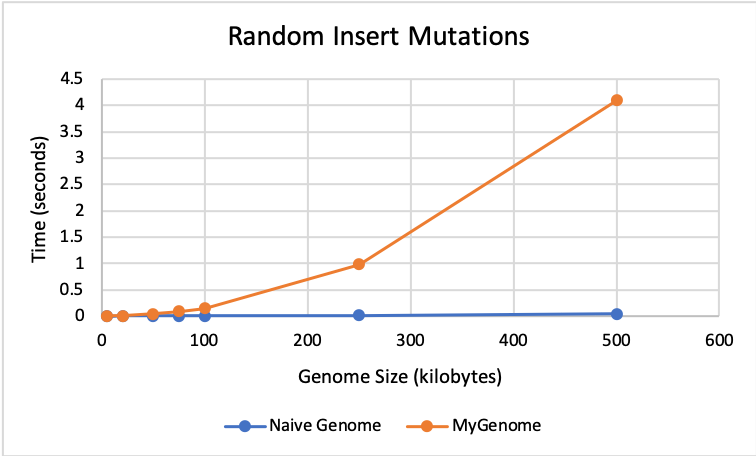

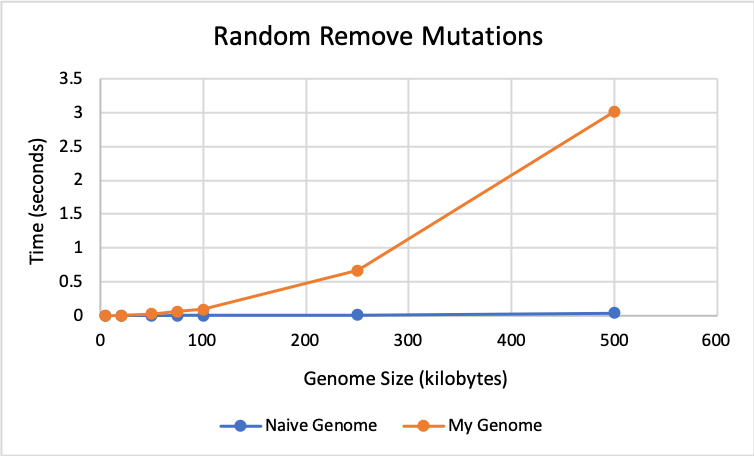

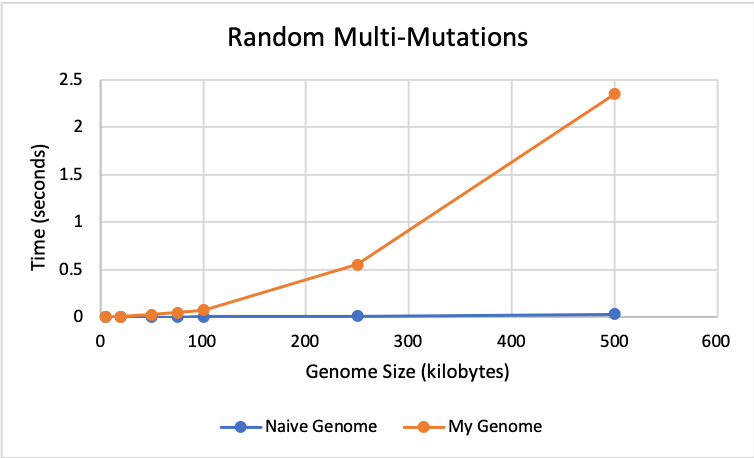

The graphs below show the performance of the naive implementation compared to my genome implementation for randomly generated mutations. These tests have been performed on size 5000, 20000, 50000, 75000, 100000, 250000, and 500000 genomes. All of these tests have been performed with the same mutation rate, 0.005.

🔗 Overwrite Results:

The graph below shows that my genome and the naive genome perform almost identically for overwrite mutations until size 20K. However, after this, the two genomes are still very close in time, but the naive genome is slightly faster.

🔗 Insert Results:

The graph below shows that my genome and the naive genome perform almost identically for insert mutations until size 100K. After this, the naive genome performs faster with times closer to 0.

🔗 Remove Results:

The graph below shows that my genome and the naive genome perform almost identically for remove mutations until size 100K. After this, the naive genome performs faster with times closer to 0.

🔗 Multiple Mutations Results:

This graph shows the performance of both genomes for random multi-mutations, which consist of overwrite, insert, and remove mutations. Both genomes perform almost identically until size 100K. After this, the naive genome performs faster with times closer to 0.

🔗 Performance Analysis:

As seen in the graphs above, my genome implementation performs very closely to the naive implementation in terms of time until size 100K. After this size, the naive implementation becomes faster for all of the mutation types. However, my implementation should save memory compared to the naive implementation because it does not store all values for every genome. Instead, it only stores a shared pointer to the parent genome and the changelogging structures (changelog and offset map).

🔗 Future Optimizations:

- To “reset” a genome in my current implementation:

- The current genome values are reconstructed from the changelogging structures, and the parent now points to the current genome.

- The changelog and offset map need to be cleared.

- Because reconstructing the entire genome takes a long time, reset is not called very often currently. This leads to changelogs and offset maps eventually becoming extremely large and causing significant overhead.

- As a result, potential optimizations could include creating a faster method to reset the genome.

🔗 Closing:

- This summer, in addition to learning a lot about C++, I have also gotten the opportunity to explore how cross-disciplinary computer science really is. This project has given me a great opportunity to expand my software development skills by creating digital genomes for organisms in an artificial life platform.

- I’ve really enjoyed working on this project with a great team of participants and mentors. It’s been so helpful to have a team to collaborate with, debug with, bounce ideas off of, and learn from. Each participant in my team implemented a different algorithm for this problem in order to test out multiple diffferent solutions. I’m really excited to have contributed to advancing genomes in MABE through my project this summer. I can’t wait to see how not only genomes but all parts of MABE will continue to evolve (pun intended😂) in the future! Thank you to my wonderful mentors and great teammates who I’ve listed below! Thank you also to the entire WAVES team who has made this summer program’s experience so amazing!

🔗 Team MABE 🎉

- Mentors: Clifford Bohm, Jory Schossau, Jose Hernandez

- Teammates: Stephanie Zendejo, Tetiana Dadakova, Victoria Cao, Jamell Dacon