Development of MABE2

🔗 Introduction

![]() To quote the Github for MABE2, “MABE is a software framework deigned to easily build and customize software for evolutionary computation or artificial life”. The resulting systems should be useful for studying evolutionary dynamics, solving complex problems, comparing evolving systems, or exploring the open-ended power of evolution.

To quote the Github for MABE2, “MABE is a software framework deigned to easily build and customize software for evolutionary computation or artificial life”. The resulting systems should be useful for studying evolutionary dynamics, solving complex problems, comparing evolving systems, or exploring the open-ended power of evolution.

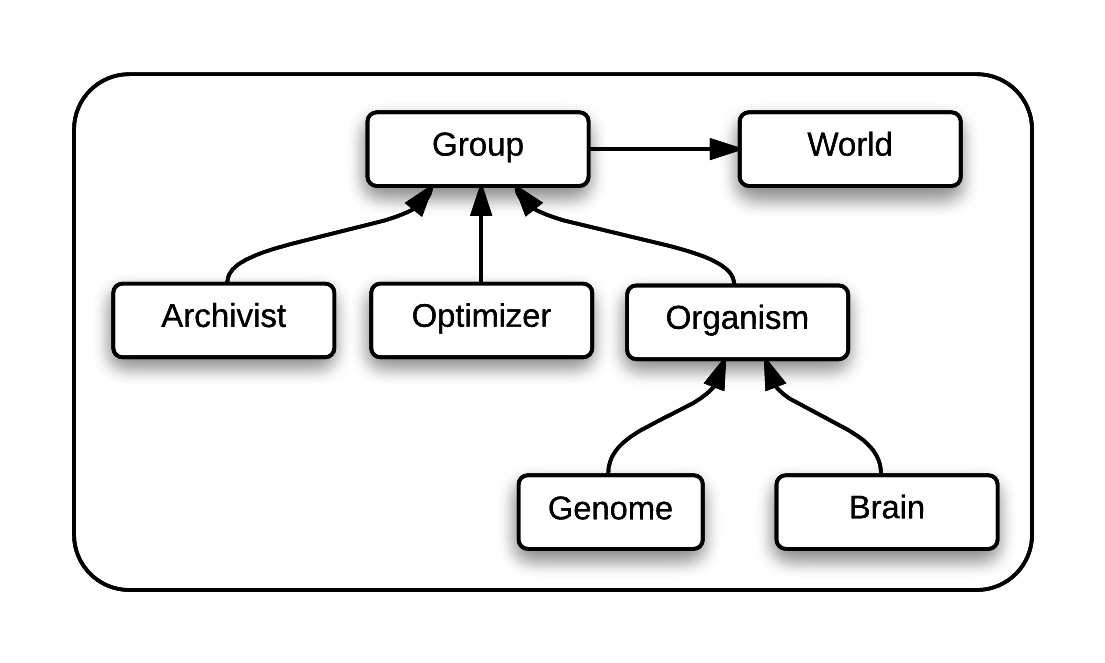

MABE, accessible here, stands for Modular Agent-Based Evolution and was one of the first true digital evolution frameworks. It was structured in this fashion:

Though powerful, could of course be improved. The creation of the 2.0 version of MABE, called MABE2, was the focus of our project. Our main focus was on refining the underlying architecture of MABE to be more end user-friendly, particularly in designing custom experiments. The culmination of our efforts was in the creation of DynamicOrg, an Organism which was near-completely abstracted to allow for any combination of Genomes and Brains, as assigned through the config file.

Along with the abstraction of organisms, we were also able to abstract away the inner workings of genomes and brains into a TypedGenome<type> and a BasicBrain. All of these abstractions remove many technical pre-requisites that users were required to have before using MABE2. Because of this, not only are far fewer steps involved when setting up an experiment, but it also takes much less time, since the majority of designing a simple experiment should be simple plug-and-play.

For comparison, this is the structure of MABE2 when using a DynamicOrg:

To explain exactly what’s going on here, we’re going to go through Genomes, DynamicOrg, Brains, and then Evaluators.

🔗 Genomes / author: jamie

![]() Genomes in MABE2 are just repositories of mutable information. The most basic kinds of genomes are vectors of some type, and (unlike in MABE) aren’t hidden inside Organisms which manage everything about them, but they are actively added to the organism and manage themselves. This means that to mutate any Genome, the Organism just tells the Genome to mutate itself. No longer will the Organism run all the mutation functions itself, now it just delegates. This, critically, means that Organisms now no longer need to know what kinds of Genomes it will have at all.

Genomes in MABE2 are just repositories of mutable information. The most basic kinds of genomes are vectors of some type, and (unlike in MABE) aren’t hidden inside Organisms which manage everything about them, but they are actively added to the organism and manage themselves. This means that to mutate any Genome, the Organism just tells the Genome to mutate itself. No longer will the Organism run all the mutation functions itself, now it just delegates. This, critically, means that Organisms now no longer need to know what kinds of Genomes it will have at all.

Genomes in MABE2 are also accessed differently – regardless of what type the Genome is, it can be read from and written to as if it were made of doubles, ints, bytes, or bits. Multiple values in a Genome can also be read from and written to in a single function call, and can be “scaled”, where what you see is automatically scaled to whatever the Genome’s actual range of values is.

Moreover, Genomes are often handled through the Genome::Head class, which allows for easy and abstract use of Genomes. Heads move along a Genome, and through a Head, any Genome operation can be accomplished, including searching (for values, ranges, multiple values, and ranges of multiple values) and all aforementioned reads and writes.

This means that it is often beneficial to pass Genomes as Heads if you want to be as generic as possible while still allowing full functionality of the Genome.

The most important part of a Genome is the mutate function. Here’s an example of a very simple mutate function for a vector of bits which first calculates a number of bits to flip according to a mutation rate, and then randomly flips that number of bits:

size_t Mutate(emp::Random & random) override { // receives a random number generator

// if we haven't configured the mutation sites yet, do so and set up the binomial distribution

if (mut_sites.GetSize() != data.size()) {

mut_dist.Setup(mut_p, data.size());

mut_sites.resize(data.size());

}

// get the number of mutations

const size_t num_muts = mut_dist.PickRandom(random);

if (num_muts == 0) return 0;

if (num_muts == 1) {

const size_t pos = random.GetUInt(data.size());

data.Toggle(pos); // swaps the bit

return 1;

}

// Only remaining option is num_muts > 1.

mut_sites.Clear();

for (size_t i = 0; i < num_muts; i++) {

const size_t pos = random.GetUInt(data.size());

if (mut_sites[pos]) { --i; continue; } // duplicate position; try again.

mut_sites.Set(pos); // sets each site of mutation to 1

}

data ^= mut_sites; // computes an exclusive or with the vector of bits and the mutation position vector

return num_muts;

}

Naturally, there are many more ways to mutate a Genome, particularly if the Genome is a vector of integers or doubles. If you want to make a Genome that mutates in a specific fashion, you’ll have to manage your Genomes with a Genome::Head as talked about above.

🔗 DynamicOrg / author: mitchell and jamie

![]() In MABE2, an Organism can be thought of as a box which contains some number of Genomes and some number of Brains. An Organism has three main functions:

In MABE2, an Organism can be thought of as a box which contains some number of Genomes and some number of Brains. An Organism has three main functions:

- An Organism needs to be able to copy itself to form one or more children.

- An Organism needs to be able to mutate itself in some way for evolution to happen.

- An Organism needs to return some kind of object which consists of all the data the Evaluator needs.

Of course, different Organisms can handle things differently, so for example an Organism in MABE (call it a BitOrg) could consist entirely of one TypedGenome<bool>, which is a Genome that is composed entirely of bits. It can copy that whenever it reproduces, it can flip some random number of bits every time it mutates, and it can simply return the bits of that Genome in a BitVector (a specialized vector of bits which Empirical uses in place of std::BitMaps and std::vector<bool>s).

But what’s a DynamicOrg? Well, a DynamicOrg is an Organism that is nearly totally built by the config file. Unlike our previous example, where the BitOrg knew it had a Genome of bits and how to mutate and return it, a DynamicOrg can’t. Specifying Genomes is relatively easy, since they’re all completely self-contained, but the Brains pose a more significant challenge, which is why we’ll be discussing them in the section after this.

Now, a DynamicOrg must necessarily be significantly less restrictive. Copying itself is fine, we just copy all its Genomes and Brains. Mutations are also reasonably simple, since all we need to do is mutate every Genome in it. But how on earth do we know what to return? Simply put, we don’t, so we just want to return an emp::DataMap. The Evaluator knows what kind of output to look for, so we let it handle extracting the necessary information from the data map. The Brains then all edit this emp::DataMap in order, in whatever way they are designed to do.

In the config file, this means all a DynamicOrg needs is a list of names of all the Genomes and Brains it will contain. So long as all these Genomes and Brains are properly named, this will work seamlessly. Each specific TypedGenome<type> will also come with specific parameters that appear in the .mabe file. Parameters like mutation probabilities, max/min values, and initially starting randomized or not, allow very specific experiments to be created.

The most important part of DynamicOrg is GenerateOutput().

void GenerateOutput() override {

emp::DataMap map;

map.Set<emp::vector<emp::Ptr<Genome>>>("genomes", genome_vec);

map.Set<emp::Ptr<emp::DataMap>>("data_map", & GetDataMap());

map.Set<emp::Ptr<emp::DataMap>>("output", & map);

for (size_t i = 0; i < brain_vec.size(); i++) {

brain_vec[i]->rebuild(map);

brain_vec[i]->process(map);

}

SetVar<emp::DataMap>(SharedData().output_name, map);

}

Essentially, the Brains get sent a DataMap of the Genomes, the DynamicOrg’s own DataMap, an output DataMap, and (not seen here) the output name. Then, each Brain builds itself (which most Brains don’t do) and then processes the data. Each Brain writes its outputs to the output DataMap, which each Brain can also read from as well, allowing for communication of a kind. Critically, this output DataMap is the only thing the Evaluator gets, and so is the only part of the DynamicOrg which it can see.

🔗 Brains / author: jamie

![]() Brains are the processors of all the Genomes in an Organism. They are only ever accessed through their process function, which takes an emp::DataMap and then converts the Genome into information that Evaluators can understand and interpret. In DynamicOrg in particular, they are all given a DataMap containing the Genomes in the DynamicOrg, and as each Brain will know which Genomes matter for its calculations, it will then access those Genomes, process them, and write its output to the DataMap.

Brains are the processors of all the Genomes in an Organism. They are only ever accessed through their process function, which takes an emp::DataMap and then converts the Genome into information that Evaluators can understand and interpret. In DynamicOrg in particular, they are all given a DataMap containing the Genomes in the DynamicOrg, and as each Brain will know which Genomes matter for its calculations, it will then access those Genomes, process them, and write its output to the DataMap.

The Brain will be configured with the names of the Genomes it works with, along with the name of its output. This means that you can make identical Brains which still deal with different Genomes and write their outputs to different addresses in the DataMap.

Many Brains, such as Markov Brains, are built from Genomes themselves, and this also occurs in the process function. This allows for Brains that evolve over time, and the Evaluator can either receive the Brain itself or whatever decision-making process it has built from the Genomes the Brain was given.

Here’s a look at the Process() function.

void process(emp::DataMap org_map) override {

SetVar<Genome::Head>(GetOutput(org_map), GetOutputName(org_map), Genome::Head(*(GetGenomes(org_map)[genome_indices[0]])));

}

This is a very simple Brain: it takes the first Genome associated with it and returns a Head to that Genome, writing it in the output DataMap with the same name that the output DataMap is written in the DynamicOrg’s DataMap. This is the “default” brain, which is useful for any experiment where you want to give the Evaluator an entire Genome.

🔗 Evaluators / author: jamie

![]() An Evaluator is, perhaps, the thing most users will spend the most time with for their custom experiments. In any evolutionary situation, Organisms will need to be evaluated on whatever traits they are supposed to be evolving, and the Evaluator assigns their fitness value from whatever outputs the Brains provide.

An Evaluator is, perhaps, the thing most users will spend the most time with for their custom experiments. In any evolutionary situation, Organisms will need to be evaluated on whatever traits they are supposed to be evolving, and the Evaluator assigns their fitness value from whatever outputs the Brains provide.

When coding an Evaluator, the most important thing is to make sure that, for whatever inputs your evaluate function requires, you’ve got Brains that can supply it. They’re configured in the same way that Brains and Genomes are, by being given a list of input names that correspond to the types that the Evaluator is expecting.

We did not make many changes to the Evaluator model, aside from making it compatible with DynamicOrg’s, which in turn made them significantly easier to customize since every DynamicOrg Evaluator follows the same steps:

- Get the emp::DataMap - This is boilerplate for every DynamicOrg evaluator and can be copied from other evaluators. DataMap will contain all the output from the organisms brain. And the brains output is what needs to be evaluated.

- Get all the input values you want from it - Simply access the DataMap with GetVar

- Calculate fitness from them - Implement any custom function for calculating fitness. Ex: counting 1s or pattern matching

- Return fitness - Make sure that function actually returns your calculated fitness.

And here’s an example of those exact steps, for a very simple Evaluator that just counts the number of ones (or zeros) in a vector of bits. The function in question here is OnUpdate().

void OnUpdate(size_t /* update */) override {

emp_assert(control.GetNumPopulations() >= 1);

// Loop through the population and evaluate each organism.

double max_fitness = 0.0;

emp::Ptr<Organism> max_org = nullptr;

mabe::Collection alive_collect( target_collect.GetAlive() );

for (Organism & org : alive_collect) {

// Make sure this organism has its bit sequence ready for us to access.

org.GenerateOutput();

emp::DataMap dm = org.GetVar<emp::DataMap>(bits_trait);

Genome::Head head = dm.Get<Genome::Head>(bits_trait);

double fitness = 0.0;

double total = 0.0;

while (head.IsValid()) {

fitness += head.ReadBit();

total += 1;

}

// If we were supposed to count zeros, subtract ones count from total number of bits.

if (count_type == 0) fitness = total - fitness;

// Store the count on the organism in the fitness trait.

org.SetVar<double>(fitness_trait, fitness);

if (fitness > max_fitness || !max_org) {

max_fitness = fitness;

max_org = &org;

}

}

std::cout << "Max " << fitness_trait << " = " << max_fitness << std::endl;

}

The code shown above is the OnUpdate() function on an evaluator. It is called after every generation, and it calculates the fitness for every organisms in the generation, keeping track of the most fit one.

The important thing here (and the thing which you will likely need) to edit for any custom experiment is this bit of code:

Genome::Head head = dm.Get<Genome::Head>(bits_trait);

double fitness = 0.0;

double total = 0.0;

while (head.IsValid()) {

fitness += head.ReadBit();

total += 1;

}

// If we were supposed to count zeros, subtract ones count from total number of bits.

if (count_type == 0) fitness = total - fitness;

After we generate the output, get its DataMap, and acquire the output DataMap from it, we have the actually unique part about the Evaluator. We grab the Head from the output DataMap (remember, we put it there with the previous example Brain!) and then we compute and set the fitness. You can start to see how any experiment you might want to run involving evolving a vector of bits towards a particular quality is practically trivial to write, since all you’d need to do is edit the few lines of code that actually calculate the fitness. Trying out different Genomes, Brains, and configuations thereof on that problem is then incredibly easy, since each trial is simply a tweak of the config file.

🔗 Tutorial - Creating and running a custom experiment using DynamicOrg

![]() Aagos (Auto-Adaptive Genetic Organization System), is a digital evolution experiment designed to show how high and low environmental change promote the evolution of segregated or non-segregated genes. It consists of N K-long genes in a circular genome that can undergo insertion/deletion/in-place mutations, as well as gene move mutations. When a gene move mutation occurs, the gene randomly picks a new starting position in the genome. There is a maximum and minimum length the genome can grow/shrink to, and fitness is calculated by comparing the N genes to a set of gene targets that act as the environment. As a demonstration of DynamicOrg and its usefulness, we will show the steps involved in implementing Aagos using DynamicOrg.

Aagos (Auto-Adaptive Genetic Organization System), is a digital evolution experiment designed to show how high and low environmental change promote the evolution of segregated or non-segregated genes. It consists of N K-long genes in a circular genome that can undergo insertion/deletion/in-place mutations, as well as gene move mutations. When a gene move mutation occurs, the gene randomly picks a new starting position in the genome. There is a maximum and minimum length the genome can grow/shrink to, and fitness is calculated by comparing the N genes to a set of gene targets that act as the environment. As a demonstration of DynamicOrg and its usefulness, we will show the steps involved in implementing Aagos using DynamicOrg.

Below is a list of possible steps a user could take when implementing a custom experiment. For Aagos, only steps 1, 2 and 3 are required.

- Write the Evaluator. (almost always necessary)

- Set up the config.

- Write the fitness calculator in OnUpdate from the emp::DataMap the Organism provides after

org.GenerateOutput() - Confirm that the outputs of the Brains in the DynamicOrg are properly configured with the Evaluator.

- Write the Brain. (often necessary)

- Set up the config.

- If the Brain needs to be built in a custom fashion, customize the Rebuild() function.

- Customize the

Process()function in order to generate the desired output.

- Setup the Config File. (almost always necessary)

- Generate .mabe from .gen.

- Input parameter settings to setup experiment.

- Run the experiment.

- Write the Genome. (very rarely necessary)

- Set up the config.

- Ensure compatibility with the base class.

- Customize the

Mutate()function.

- Write the Organism. (shouldn’t be necessary except in the direst of circumstances)

- Set up the config.

- Customize the

Initialize()andMutate()functions.

Before starting, we must first make a few decisions on the exact implementation we will use. For the genome itself, we will use a TypedGenome<bool> with an initial size of 32. This genome will undergo insertion/deletion/in-place mutations and will contain the N genes. We will also use a TypedGenome<int> with a max value of our (TypedGenome<bool>.length - 1), a min value of 0, of length N. This genome will represent the N genes starting position within the genome, hence why any of its values cant exceed the current length of the genome, otherwise an out-of-bounds error would occur.

We will first write the Aagos brain. Our Aagos brain will be responsible for transforming the genome and starting positions into the N genes the evaluator will evaluate.

class AagosBrain : public Brain {

protected:

emp::vector<emp::Ptr<Genome>> genomes;

public:

AagosBrain() {};

AagosBrain(const AagosBrain &) = default;

AagosBrain(const emp::vector<emp::Ptr<Genome>> & genomes_in) : genomes(genomes_in) { }

void process(emp::DataMap org_map) override {

size_t gene_size = 8;

emp::vector<emp::BitVector> genes(genomes[0]->GetSize());

for(size_t i = 0; i < genomes[1]->GetSize(); i++) {

emp::BitVector gene(gene_size); // create empty bit vector which will hold separated genes

gene.Clear(); // this function apparently only works for doubles right now, so I will manually set each bit to 0

size_t current_position = genomes[0]->ReadInt(i); // start current position at genes start position

for (size_t j = 0; j < gene_size; j++) {

if (genomes[1]->ReadBit(current_position)) { // copy bit out of bits at current_position into gene at j

gene.Toggle(j);

}

current_position++; // increase current position in genome

if(current_position == genomes[1]->GetSize()) { // if current_position goes out of range, reset to 0

current_position = 0;

}

genes[i] = gene; // insert constructed gene into output vector

}

org_map.Get<emp::Ptr<Organism>>("organism")->SetVar<emp::vector<emp::BitVector>>(org_map.Get<std::string>("output_name"), genes);

}

};

Our brain receives a vector of pointers to Genomes, with the first in the list being our starting positions, and the second being the genome itself. From here its as simple as extracting all the genes from the genome, and then storing them in a vector of bit vectors that our evaluator will receive.

Since Aagos fitness is calculated by comparing the N genes in an organism to the environment gene-targets, we will need to write an evaluator that does this. From our brain, we know we are receiving a vector of bit vectors representing the N genes. To make things simpler, our environment will ALSO consist of a vector of bit vectors.

void OnUpdate(size_t update) override {

emp_assert(control.GetNumPopulations() >= 1);

// every 'change_frequency', mutate the environment

if (update % change_frequency == 0) {

mutateEnvironment();

}

// Loop through the population and evaluate each organism.

double max_fitness = 0.0;

emp::Ptr<Organism> max_org = nullptr;

mabe::Collection alive_collect( target_collect.GetAlive() );

for (Organism & org : alive_collect) {

// Make sure this organism has its bit sequence ready for us to access.

org.GenerateOutput();

// get genome from organism

const emp::vector<emp::BitVector> & gene_set = org.GetVar<emp::vector<emp::BitVector>>(bits_trait);

// start fitness at 0

double fitness = 0.0;

for (size_t i = 0; i < gene_targets.size(); i++) {

double matching_bits = 0.0;

for (size_t j = 0; j < gene_size; j++) {

if (gene_set[i][j] == gene_targets[i][j]) {

matching_bits++;

}

}

double gene_fitness = matching_bits / gene_size;

fitness += gene_fitness;

}

fitness = (fitness / gene_targets.size()) * 100;

// Store the count on the organism in the fitness trait.

org.SetVar<double>(fitness_trait, fitness);

if (fitness > max_fitness) {

max_fitness = fitness;

}

}

std::cout << "Max " << fitness_trait << " = " << max_fitness << std::endl;

}

On every update of the evaluator, we mutate the environment gene-targets if necessary. We then simply compare each gene to each gene target. The fitness of our organism is simply the proportion of matching bits. For example, if our first gene is 01011101, and our first gene target is 01010001, then the fitness for that gene is 6/8. The total fitness is simply the sum of all gene matching proportions.

The last and final step is to setup the config file.

TypedGenome<bool> bit_genome { // Holds a genome of true/false

length = 32; // Length of genome

mut_prob = 0.003; // Chance for a mutation to occur

init_random = 1; // Should we randomize ancestor? (0 = all zeros)

}

TypedGenome<int> int_genome { // Holds a genome of ints

length = 8; // Length of genome

min_val = 0; // Minimum value for specific int

max_val = bit_genome.length; // Maximum value for specific int

mut_prob = 0.003; // Chance for a mutation to occur

init_random = 1; // Should we randomize ancestor? (0 = all min value)

}

AagosBrain aagos_brain { // Splits a TypedGenome<bool> into num_genes genes using a TypedGenome<int> that represents start positions

num_genes = int_genome.length;// Number of genes to create

gene_size = 8; // Size of each gene

genomes = "bit_genome,int_genome";// Genomes AagosBrain will work with

}

EvalAagos eval_ag { // Evaluate a genome by its proportion of bits matching the gene targets.

target = "main_pop"; // Which population(s) should we evaluate?

bits_trait = "bits"; // Which trait stores the bit sequence to evaluate?

fitness_trait = "fitness"; // Which trait should we store NK fitness in?

}

DynamicOrg aagos_org { // Dynamic organism that can take any number of genomes and brains.

genomes = "bit_genome,int_genome";// Types of genomes to use.

brains = "aagos_brain"; // Types of brains to use.

}

We first initialize a TypedGenome<bool> and TypedGenome<int> as our primary genomes, and setting their values accordingly. Next we initialize the AagosBrain, passing it the genomes it needs to evaluate, followed by our evaluator EvalAagos. Then we just plug everything into DynamicOrg.

🔗 Conclusion

![]() From these steps, it is clear that the end user can more easily and more efficiently create custom experiments to suit nearly any research goal. Where previously almost any experiment would have required significant editing of numerous files, now most experiments can be completed simply by creating a new Evaluator and editing the config file. In addition, experiments involving trying different forms of evolution to solve the same problem are made drastically easier, as the only difference between those experiments would be in the config files. Finally, the more modular nature of this new framework lends itself very well to collaboration, where a Brain one person makes could easily be used in another person’s Evaluator and, with how Genomes are so standardized by Genome::Head, using a new Genome type in the place of a more basic Genome would be trivial.

From these steps, it is clear that the end user can more easily and more efficiently create custom experiments to suit nearly any research goal. Where previously almost any experiment would have required significant editing of numerous files, now most experiments can be completed simply by creating a new Evaluator and editing the config file. In addition, experiments involving trying different forms of evolution to solve the same problem are made drastically easier, as the only difference between those experiments would be in the config files. Finally, the more modular nature of this new framework lends itself very well to collaboration, where a Brain one person makes could easily be used in another person’s Evaluator and, with how Genomes are so standardized by Genome::Head, using a new Genome type in the place of a more basic Genome would be trivial.

Before our work, it took an average of 6 steps in about 30 minutes of coding to create a completely custom experiment. On top of that, to achieve that speed, you would need deep C++ knowledge, experience using the Empirical library, and a good understanding of how genomes and brain are represented in code. After our work, as stated above, an experiment can be created in as little as two steps, with a maximum of 3 steps. Those steps being creating a custom evaluator, creating a custom brain, and then simply plugging everything together in the config file.

In short, our work has greatly simplified the end user experience and streamlined the research process for all who would use MABE2 in the future.

🔗 Future plans / Work we didn’t complete

![]() Unfortunately, we simply did not have the time to do everything we wanted. As such, these are the remaining issues:

Unfortunately, we simply did not have the time to do everything we wanted. As such, these are the remaining issues:

- The config system for Brains and Genomes does not yet work. The structure should be similar to how Organisms are, with each Genome having a name and the various pertinent values (such as mutation rate and min/max values) and each Brain having a name, the names of the Genomes it will use, and whatever stats it will have (such as Markov Brains needing the size of their gates and all Brains having the name of their outputs).

- This is the desired form of DynamicOrg and is really the key to making it as seamless as possible. It allows most of the users work to be done inside the config file instead of in C++.

- Brains should be implemented to actually use this information.

- Brains should have their own parameters and settings that appear in the config file.

- BasicBrains, MarkovBrains, and TypedGenomes should all be put in their own files.

- For organizational purposes.

- The MarkovBrain should be properly tested and the hardcoded values should be made easily configurable via the config file.

- Similar to issue 1, it should work in the config file.

- As part of item 4, GenomeManager and BrainManager classes should be created to act as OrganismManagers do for Genomes and Brains. Ideally, these would all be turned into one big Manager class.

- This is how issue 1 will be achieved, through the implementation of a generic manager class so that essentially any type can be placed into the config system.

- The more complicated mutation types should be added to TypedGenome with configuration options to set the rate for each of them.

- Genomes should be highly customizable to allow highly custom experiments to be run. We want to keep the user out of the C++ code as much as possible.

- More Brain types should be added by default.

- We currently only have BasicBrains and MarkovBrains, more should be included so that users have to do as little work as possible.

🔗 Acknowledgements

Mentors: Dr. Charles Ofria & Cliff Bohm

Participants: Mitchell Johnson & Jamie Schmidt

Charles Ofria and Cliff Bohm conceived and planned the idea of DynamicOrg. They both then contributed to the design and implementation of DynamicOrg. The majority of implementation of DynamicOrg was created by Jamie Schmidt with help from Mitchell Johnson.

Jamie Schmidt wrote the sections on Brains, Genomes, Evaluators, and Introduction. Mitchell Johnson wrote the sections on Tutorial using DynamicOrg, and Conclusion. Jamie Schmidt and Mitchell Johnson worked together on sections Future plans, and DynamicOrg.

Thank you to our amazing mentors!

This work is supported through Active LENS: Learning Evolution and the Nature of Science using Evolution in Action (NSF IUSE #1432563). Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.