BitVector Optimizations and DataMap Features

🔗 BitVector Optimizations and DataMap Functionality Improvements

🔗 Introduction

For my project, I worked with the Empirical library, a scientific software library. I primarily focused on BitVector and DataMap, two classes for data storage.

BitVector is, as the name suggests, a Vector of bits (though it’s actually bytes). The standard library has something similar, std::BitMap, but it is incapable of bit operations like NOT or XOR and has a size which must be fixed at compile time. BitVector, on the other hand, has bit operation support and can be resized during runtime. However, BitVector did not contain what is known as a “small optimization”, that being an optimization where a class has all of its data stored in its own memory, without relying on a pointer elsewhere.

DataMap is similar to a regular map, but is heavily optimized for scientific computing. All of its memory is stored in a single array of bytes, and layout information (detailing what is stored where) can be shared between separate DataMaps. However, DataMap did not contain a way to store a reference to another object in the same place as the object itself. In other words, given a variable in a DataMap, you couldn’t set that variable to be a reference elsewhere. When you added that variable, you had to choose whether it was going to be the variable itself or a pointer to that variable.

🔗 BitVector

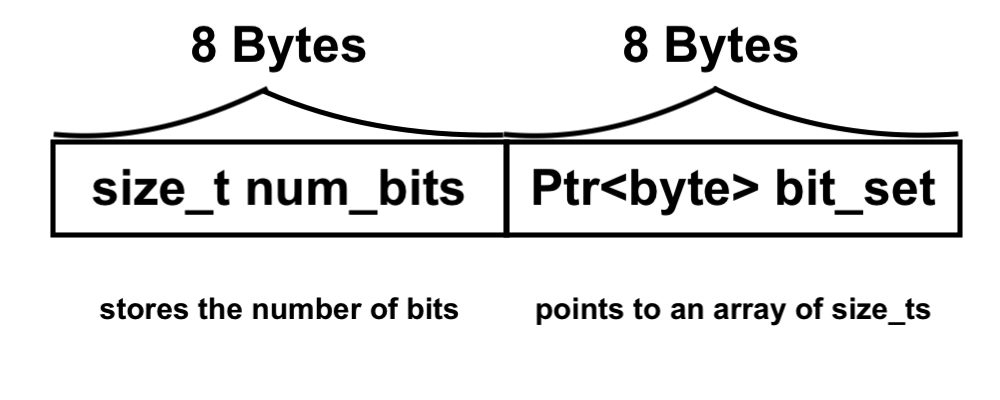

A BitVector is an eight-byte size and an eight-byte pointer to an array of bytes. They are generally constructed with a certain length, and all of the bits are set to 0 or 1 based on a boolean you may choose to supply to the constructor. After that, you can treat it as an array of bits, indexing with Get and Set (or their respective byte and uint variants). You can also use bit operations such as BitVector::AND(BitVector bv2) and BitVector::OR(BitVector bv2), which return the result, or bit operations such as BitVector::AND_SELF(BitVector bv2) and BitVector::OR_SELF(BitVector bv2) which return the result and set the BitVector to that result. If the BitVector needs to become larger or smaller, it can be resized with BitVector::Resize(size_t newSize).

Compared to indexing into an array or BitMap, a BitVector is somewhat slower. Compared to an equivalent Vector of bytes, however, it is significantly faster and has greater functionality.

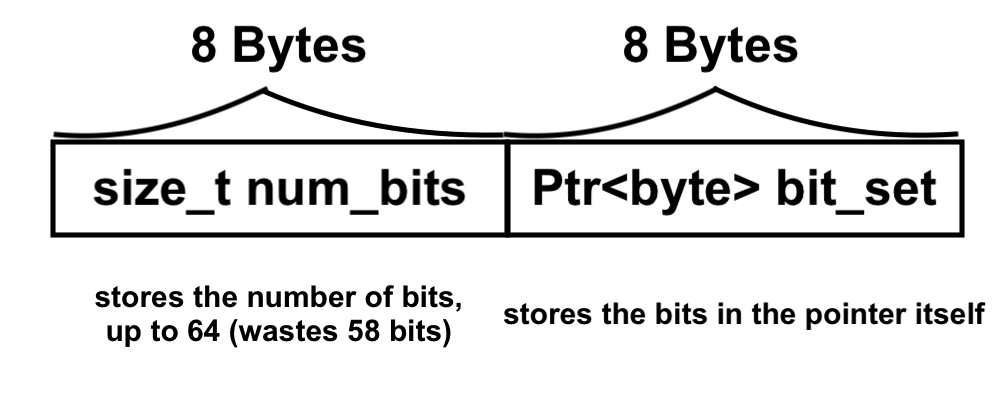

But let’s look at that pointer for a moment. Eight bytes is 64 bits, which is quite a few. Many experiments in MABE, an evolutionary learning library built upon Empirical, require fewer than that. In other words, the pointer isn’t any smaller than what it’s pointing to. So, if the size is less than or equal to 64, why have the pointer at all? Couldn’t we just replace the space in memory with 64 bits of data (or however many bits we needed)? Well, we can, and that is the small BitVector optimization.

There’s also the secondary small BitVector optimization which will involve adding an extra byte of control bits before the size and cannibalizing the eight bits of size for extra space to grant BitVector the same optimization for 128 bits and fewer.

🔗 The Small BitVector Optimizations.

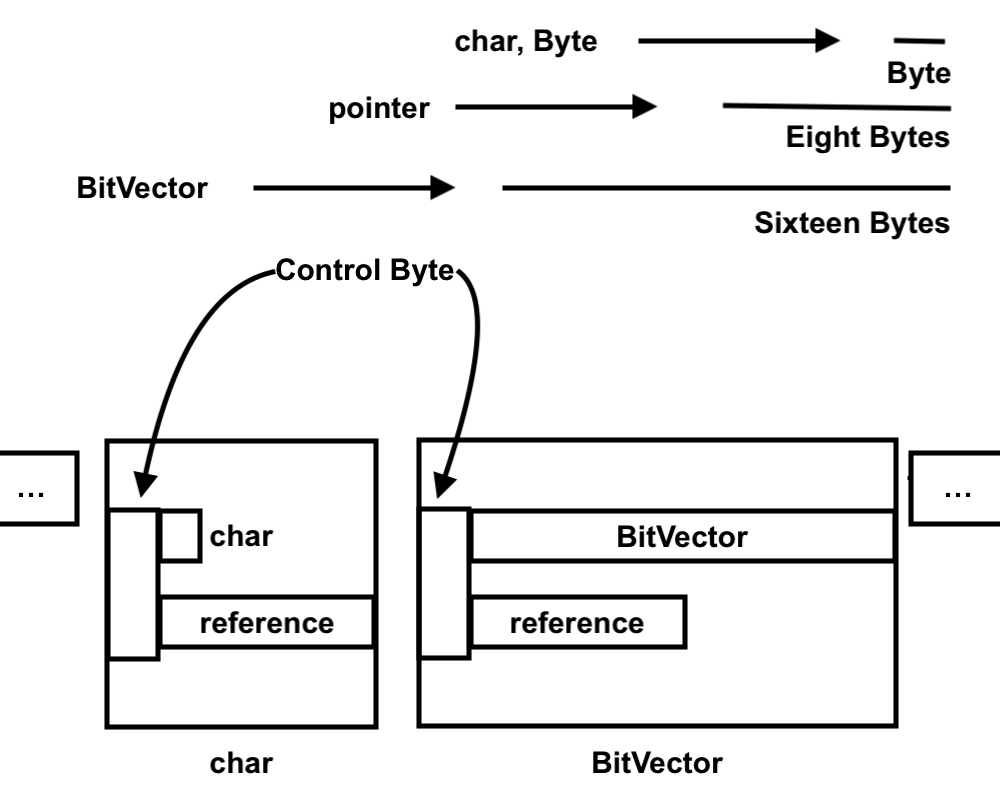

This is how a BitVector used to be structured:

And this is how I have restructured it for small BitVectors.

It looks pretty straightforward. However, there are several pitfalls which befell me, and many of them could very well befall you if you do something similar. But first, the most important function of this part of the project, BitVector::BitSetPtr(), which is called each and every time we have to access our memory:

using field_t = size_t;

size_t num_bits; ///< How many total bits are we using?

emp::Ptr<std::byte> bit_set;

/// Return the proper casting of bit_set

emp::Ptr<field_t> BitSetPtr() {

// For large bit sets, the bit_set pointer tells you where it is.

if (num_bits > SHORT_THRESHOLD) {

return bit_set.Cast<field_t>();

}

// For small bit_sets assume they all fit in the space of the bit_set pointer.

return emp::Ptr<field_t>((field_t*) &bit_set);

}

Note that our bit_set is a pointer to an array of bytes. I know it looks like a pointer to a single byte, but the emp::Ptr is a strange beast indeed and can support arrays as well. It was initialized with

bit_set = NewArrayPtr<field_t>(NumFields()).Cast<std::byte>();

if we had more than 64 bits (and it was just set to some value if we didn’t) where NumFields() just tells us how many bytes we need.

Let’s go through this line-by-line. So our function declaration returns an emp::Ptr<field_t>. An emp::Ptr is an Empirical pointer, which can be used to easily track memory when in debug mode. A field_t is a renaming of a size_t, which means that should it become necessary to make a field longer than eight bytes, we can simply change one line of code. So what our declaration says is that we’ll return a pointer to either a single field_t (the eight bytes of short BitVectors) or an array of field_ts (for the long BitVectors).

Now, if we have more bits than the SHORT_THRESHOLD (currently 64), we simply cast the pointer back to an array of field_ts, just like we casted it from an array of field_ts to an array of bytes. But if we have 64 or fewer bits, then we take a reference to bit_set, cast it to a pointer to a field_t, and then make it an emp::Ptr to a field_t.

This means that if we have more than 64 bits, we index into the pointer, and if we don’t, we simply dereference it. So we have a lot of code like:

if (num_bits > SHORT_THRESHOLD) {

return (BitSetPtr()[field_id] & (static_cast<field_t>(1) << pos_id));

}

return (*BitSetPtr().Raw() & (static_cast<field_t>(1) << pos_id));

which is the Get function.

So what could go wrong with this? Well, the fact that we are messing with pointers means that there will inevitably be some memory errors. Memory leaks, accidental dereferences, that sort of thing. And so there were, mainly with earlier versions of BitSetPtr and the move and copy constructors. Resize also posed a bit of an issue, since it is possible to cross 64 bits and go from long to short or from short to long, which requires some adjustment of how things are stored.

Once I had gotten this done, the speedups were generally quite high, but I encountered several issues in determining how high they were. My original plan was to run all of my tests on a dedicated node on MSU’s HPCC, but unfortunately that proved far more difficult than expected due to the absence of several necessary libraries. As such, I had to run my tests on my personal laptop overnight, which necessarily caused the variance in my results to be much, much higher. This variance was so high for my generalized BitVector tests, in fact, that I have no confidence in them. While the mean times of my trials do largely correlate with my predictions (with speedups for small BitVectors and (rarely) a slight slowdown for big BitVectors), I cannot in good confidence showcase them.

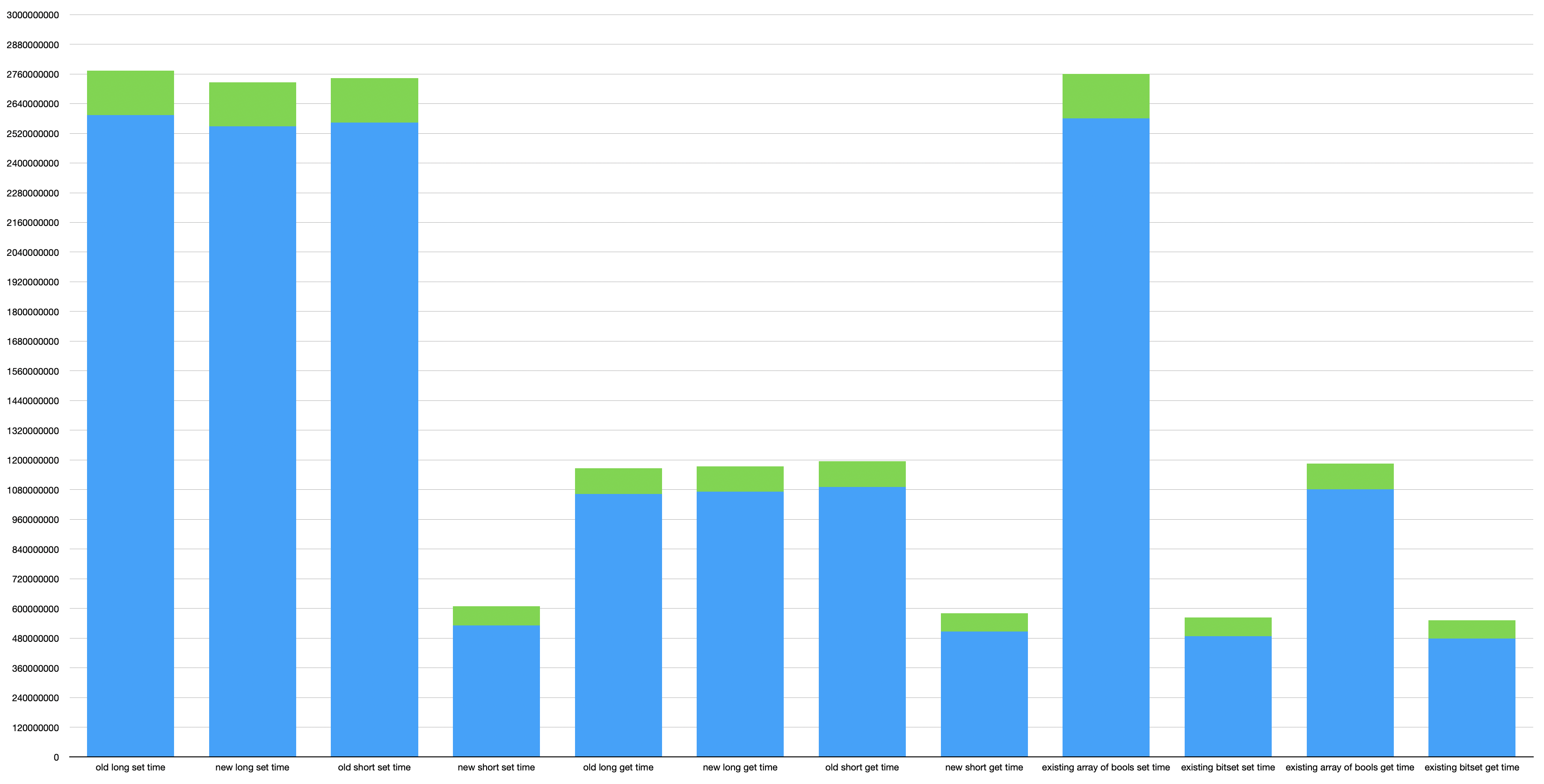

However, I did run a successful test on the most important methods: Get and Set.

In this graph, the green is my 95% confidence margin of error. The vertical axis is the mean in milliseconds of the time it took to run an individual trial, which consideted of randomly selecting a random BitVector/BitMap/array and then a random element in them several hundred million times.

As you can see, there is a considerable improvement with the small BitVector approximation which comes quite close to the std::BitSet time, while the previous times were closer to accessing an array of bools. Given that Gets and Sets are by far the bulk of calls to BitVectors, this equates to a considerable speedup.

🔗 DataMap

A DataMap is two other classes in a trench coat: a pointer to a DataLayout and a MemoryImage. Each MemoryImage belongs to one and only one DataMap, but DataLayouts can be linked to several DataMaps. The DataLayout contains information about the MemoryImage, such as the names (strings), indices (size_ts), descriptions and notes (strings), and such things as constructors and destructors for more complex objects.

The MemoryImage is a vector of bytes with each object taking up a number of them in contiguous memory. Much of the MemoryImage’s deeper workings rely on reinterpret casts and memory tricks (which I won’t go into), but the main gist of it is that it contains a region of memory which holds a series of items of various types. On the surface, however, you don’t ever need to interact with DataLayout or MemoryImage. Add variables using DataMap::AddVar<T>(string name, T value, string description, string notes), which returns a size_t which is the variable’s index in the Vector of bytes. Now, you can access that variable with DataMap::Get<T>(string name) or DataMap::Get<T>(size_t id), but the id access is significantly faster. You can also set the variable again with DataMap::Set<T>(string name, T value) or DataMap::Set<T>(size_t id, T value). There are other methods involving comparing layouts and getting types and seeing if ids and names exist, but those are far less important for the day-to-day use of DataMap.

Compared to a regular std::Map, which is a hash table, the DataMap is far more efficient if fewer additions and deletions are being made compared to sets and gets. In fact, DataMaps don’t even allow for deletions at all. As such, it is more optimized for scientific computing and the large number of accesses which are commonplace in MABE.

However, as I said before, this rigidity poses a bit of a flaw. Say you want to add a variable of type Foo to your DataMap. You call AddVar with a Foo. This Foo is added to the DataMap and now exists in DataMap’s memory. But what happens if you want to add another Foo? Well, you have to take that new Foo and replace the first Foo in DataMap’s memory. But what if this new Foo is someplace else, and can change? Well, currently, you’re out of luck. But if we take the memory DataMap gives for that new Foo, and we place a pointer there instead (with a byte of control bits, of course), we can handle this sort of situation.

🔗 The DataMap Reference Capability

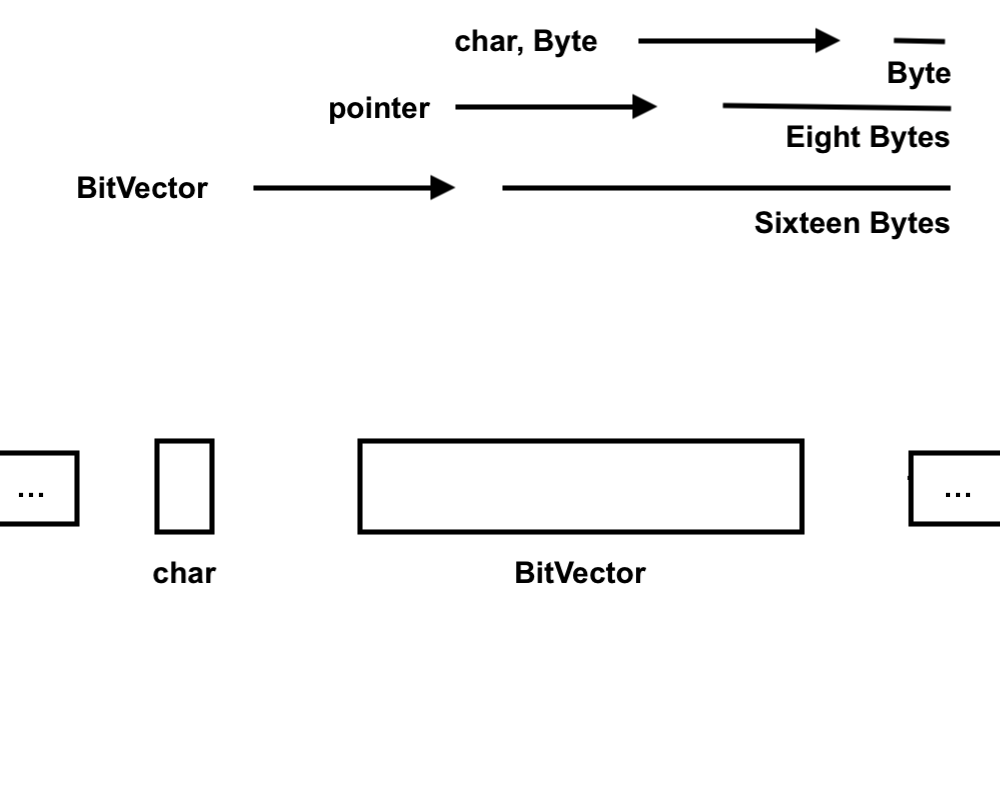

This is how a DataMap used to be structured:

And this is how I have restructured it, with the control bits only really determining if what’s stored is a reference or not.

Note that the size is determined by the size of Ptr – if we are in memory tracking mode, then a Ptr will contain more than just a ptr.

Unlike BitVector, there isn’t one piece of extremely important code. Instead, there are two, those being the functions Set and SetRef.

/// Set a variable by ID.

template <typename T> T & Set(size_t id, const T & value) {

if (memory.isRef(id)) { // if it's a reference

memory.Destruct<T>(id); // destroy the reference

memory.setRef(id, false); // set it to be not a reference

new (memory.GetPtr<T>(id+1).Raw()) T(value); // construct the value in that space

return memory.Get<T>(id); // return the value

} else {

return (Get<T>(id) = value); // just set it normally

}

}

/// Set a reference to a variable by ID.

template <typename T> T & SetRef(size_t id, T & value) {

if (!memory.isRef(id)) { // if it's not a reference

memory.Destruct<T>(id); // destroy it

memory.setRef(id, true); // set it to be a reference

new (memory.GetPtr<Ptr<T>>(id+1).Raw()) Ptr<T>(& value); // construct the reference in that space

} else {

*memory.GetPtr<Ptr<T>>(id+1) = & value; // just set it normally

}

return memory.Get<T>(id); // return the value

}

The complex bit of this code is the “new” phrase. It creates an instance of the object using the copy constructor at where the pointer to the object (which is actually a reference, but that doesn’t matter since it’s been destructed). Turns out you need to do it this way or you end up with memory leaks. That was probably the most difficult part of this project.

Now, memory is (as you would expect) a MemoryImage, and MemoryImage::Get is

/// Get proper references to an object represented in this image.

template <typename T> T & Get(size_t pos) {

if (isRef(pos)) {

return **GetPtr<Ptr<T>>(pos+1);

}

return *GetPtr<T>(pos+1);

}

As you can see, MemoryImage::Get properly indexes past the control byte into the actual memory, which means DataMap::Set and DataMap::SetRef don’t have to. This positioning is necessary, since DataMap isn’t the only thing which calls MemoryImage::Get and MemoryImage::GetPtr. I missed this, however, which led to quite a spectacular bug when I put the increment in MemoryImage::GetPtr instead.

During my testing, I used two types of values: chars and BitVectors. Chars are smaller than pointers, so I was quite keen to see if any issues would arise from them. Naturally they did, since chars (even those stored in variables) are passed into functions via temporary addresses, meaning that storing that address is useless and can give strange results, but that was a fairly straightforward fix. BitVectors are larger than pointers (but smaller than emp::Ptrs with memory tracking enabled), and I know their memory layout pretty well. In general, I used BitVectors with size 10 and all bits 0 because that was easier.

The chars worked perfectly after a while, and so (it seemed) did the BitVectors. However, I discovered that when I changed a bit in a BitVector (turning it from a 0 to a 1) everything blew up the next time I tried to add a new value. For quite some time I went through BitVector again, trying to see why this could be happening. It would be like changing a character in a string and suddenly having seemingly unrelated pointers attempt to delete unallocated memory. Eventually I did the smart thing and went into the debugger (lldb saves lives).

Just seeing where the segfaults occurred was useless, since that didn’t tell us what exactly was segfaulting. But when I used lldb to show me the values stored in the BitVector causing the problem at the time of their deletion, I discovered that, somehow, I was deleting BitVectors with a size much, much greater than 10, which called the big BitVector destructor, which tried to delete the bit_set pointer as if it pointed to an array. But this didn’t happen to any of my allocated BitVectors or any of my BitVectors which appeared in the MemoryImage. Eventually, it turned out I had made an off-by-one error in MemoryImage::Destruct which caused a shift where the destructor read from by one byte, and MemoryImage::Destruct calls MemoryImage::GetPtr, so it ended up being shifted twice, which caused the BitVector to read in the stored bits as the size.

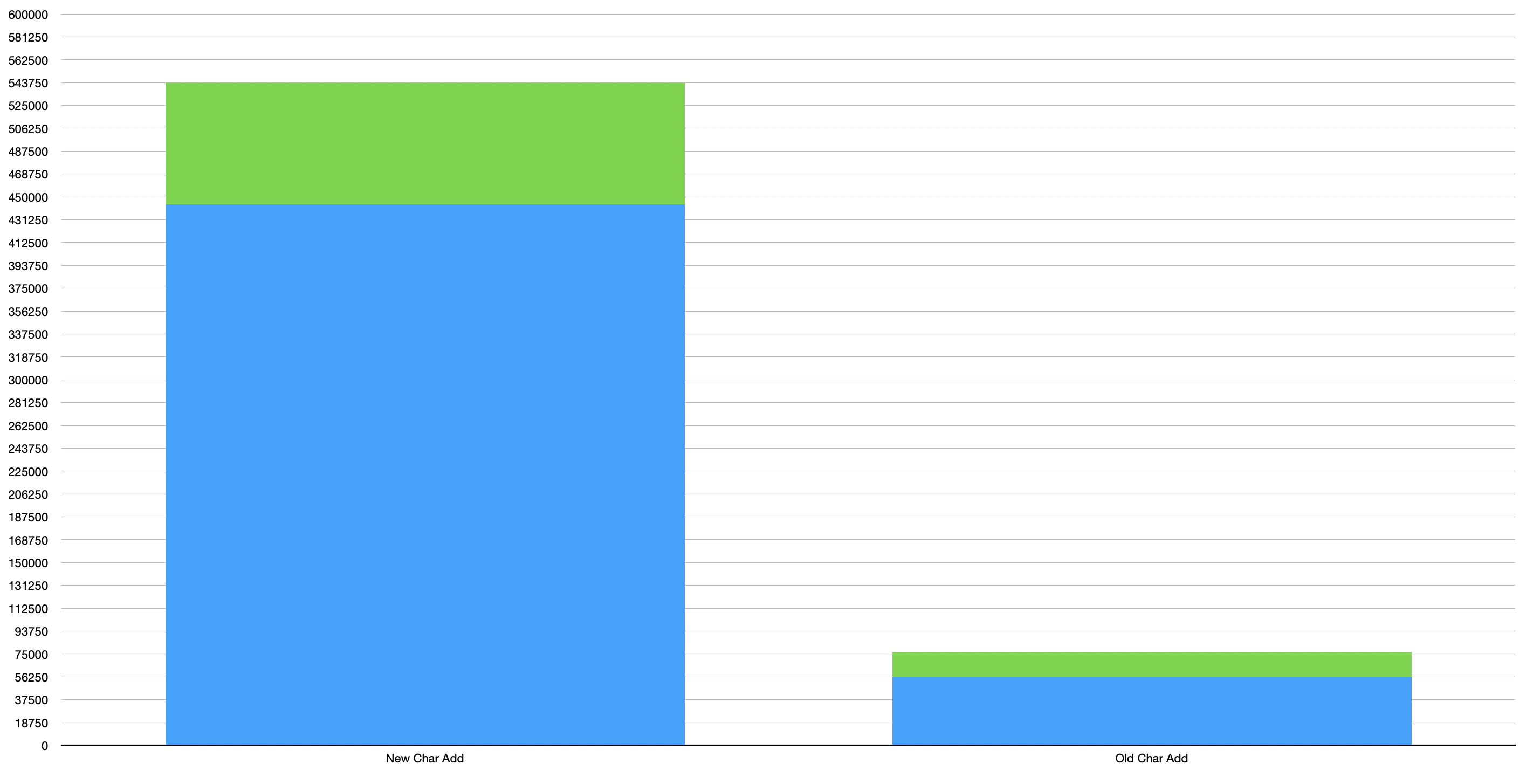

Once I had gotten this done, there wasn’t any speedup (as expected), and some methods were slowed down noticeably. In particular, adding a char took far, far longer in this new version (which requires nine bytes of memory) than the old (which required only one).

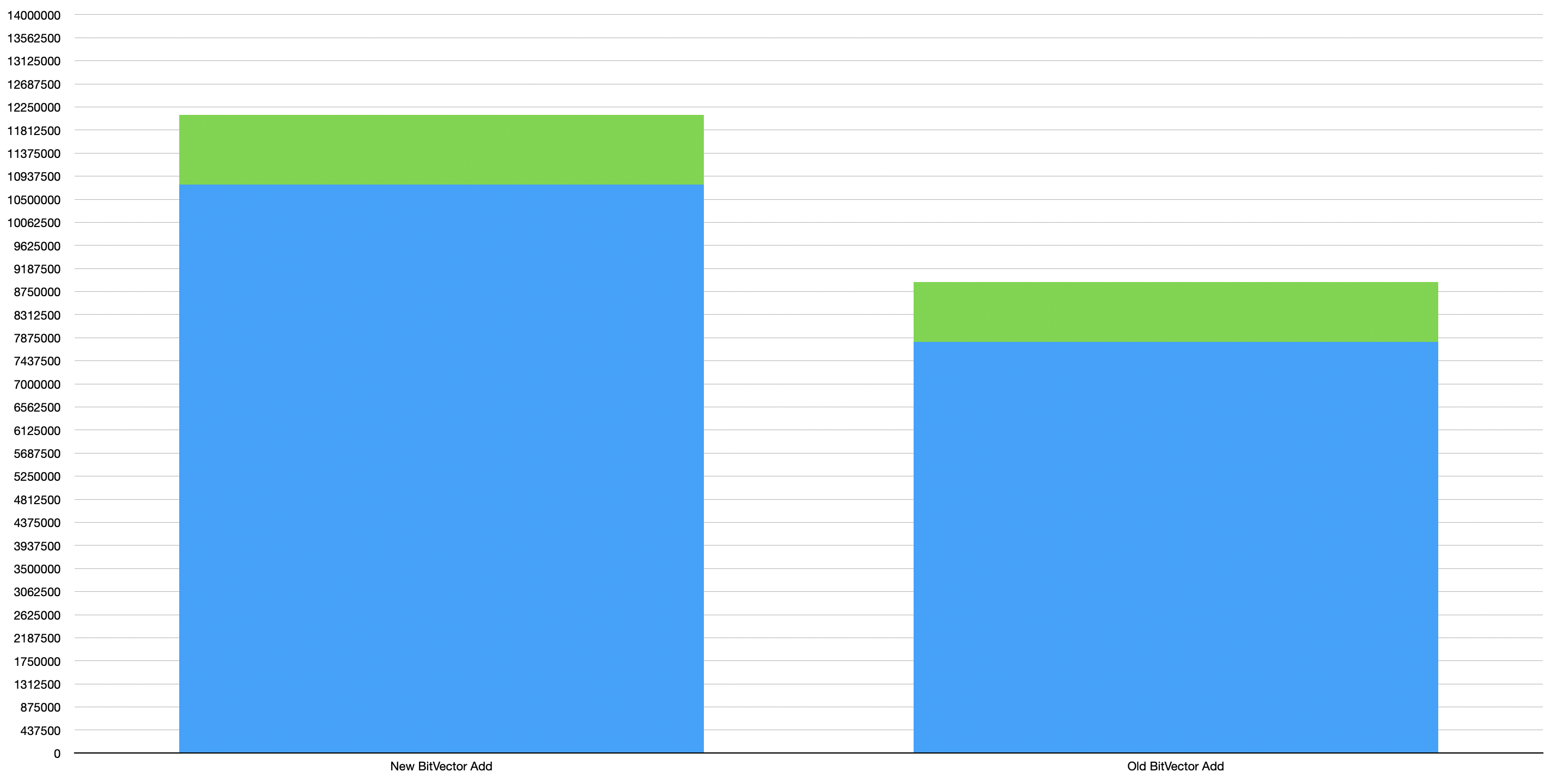

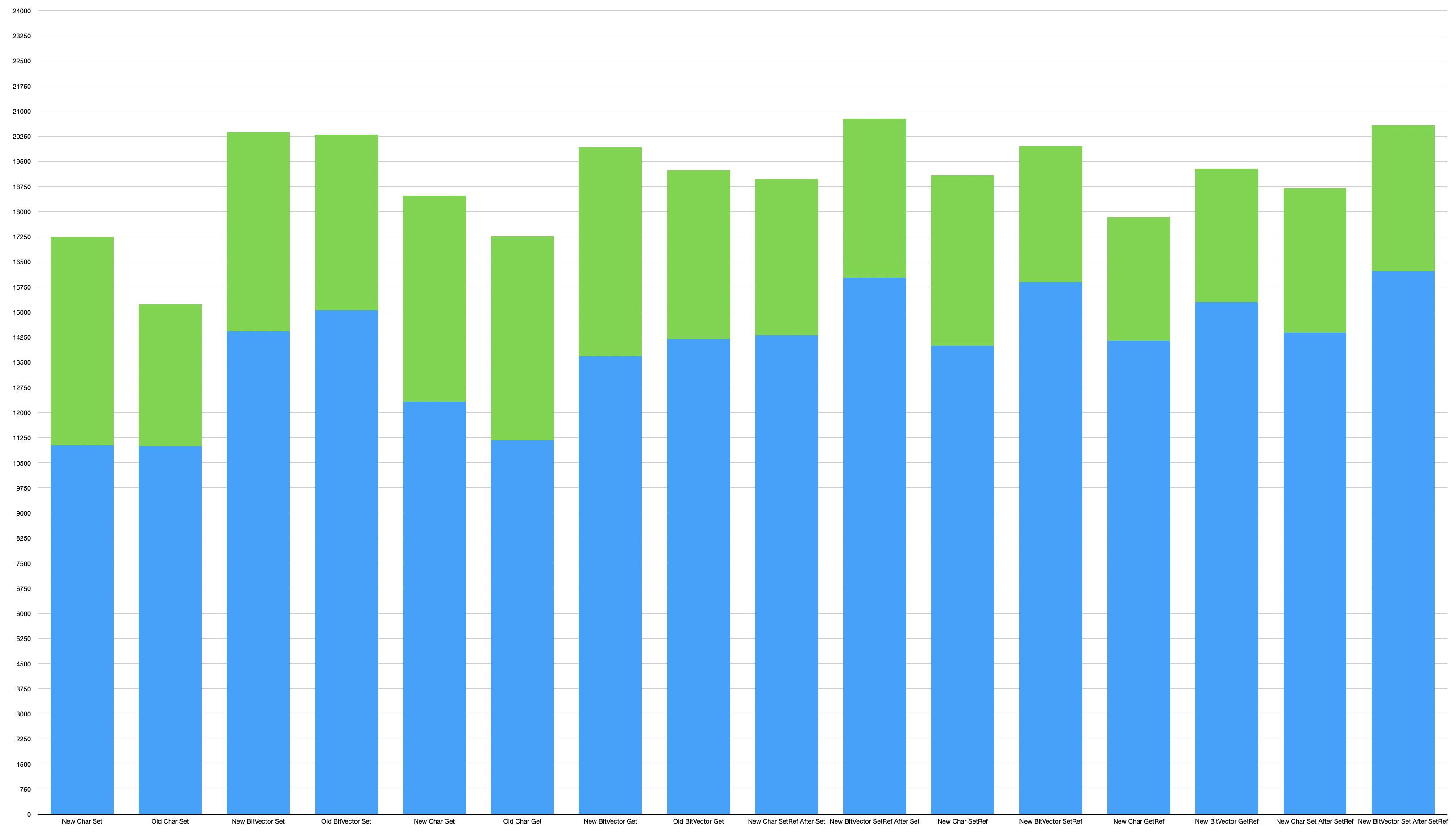

Testing the DataMap unfortunately was as difficult with the BitVector, and the variance was still far greater than I would like. So I once again focused on the most important methods and tested those.

This test showed a considerable slowdown, which makes sense as the new char allocation requires 9 bytes while the previous required just one.

This test showed a more minor slowdown, which also makes sense for the same reasons as above.

This section is somewhat more chaotic. On the plus side, at least we don’t see a drastic slowdown. In addition, we do see the expected slowdown from crossing over from a reference to a value and vice versa, and we also see that BitVector gets and sets are slower than char gets and sets. We also see that getting a reference is slower than getting a value, which is also to be expected. The main takeaway is that there is unlikely to be a noticeable slowdown from the reference feature.

🔗 Conclusion

My work improved BitVector speed considerably for BitVectors at or below 64 bits in length, making them nearly as fast as BitSets of the same size without causing any noticeable slowing down of longer BitVectors. I also implemented a significant improvement in DataMap functionality, though that did come with certain costs in efficiency, both of space and time. However, the most important methods (the ones which would be called the most often) suffered little to no slowdown.

I also learned a great deal about many advanced C++ topics (and was able to put into practice much of what I learned in my C++ course last semester), and had a great time. The projects I was given were interesting and challenging, and forced me to really think about all aspects of my code. Thanks to all of the mentors who helped run this workshop, and especially Dr. Ofria and Matthew Moreno, who helped me out a LOT over the ten weeks.

🔗 Further Work

After this workshop is over, I intend to stay on longer and finish my work on BitVector and DataMap. With unions, my mentor Dr. Ofria and I suspect that we can make both of them far simpler and, perhaps, faster. We also suspect that we can get a 128-bit small BitVector optimization with unions by adding a control byte, which would greatly improve performance for the 100 bit-long BitVectors often used with MABE. Also, we believe that we can fix a possible allignment error which could theoretically cause issues in certain unlikely circumstances. For DataMap, I intend to use unions to streamline the logic of referencing, which could make the code faster and would definitely make it easier to read.