Exploring Genome Optimizations for Digital Evolution

🔗 The Problem at Hand

Genomes are often large and on cloning and mutating those genomes, runtime on copying and memory movement operations on shift mutations takes a toll on runtime and memory consumption. When copying and mutating, offspring from the same parents will often contain stretches of identical data.

Haven't seen Pokemon?

The gif shows many evolutions from eevee! You can think of eevee like the parent genome, and the evolutions as mutated offsprings.Like in the case of eevee and it’s evolutions, if identical data between the mutations can be conserved, instead of copying the same shared gene segments to all of the mutations, running an evolution loop will ideally take up less time with less page faults. To conserve as much space as possible, optimize run time, and still give the researcher random access to the genome, I propose a lightweight genome version built off of a segmented link list of genome site locations with a random accessing indexing table.

🔗 Naive Approach

The naive approach is to have a piece of contiguous memory for every genome, to copy the whole genome for an offstring and apply shift mutations by standard memory move functions.

But why manually copy identical, or near identical, offspring when it’s much faster to point to the areas that are the same and create local mutations when needed? The downsides to creating a new genome for every organism is apparent; if the entropy between genomes within the population is low, then condensing non-unique data will lower memory consumption and optimize shifts on large scale genomes.

🔗 The Proposed Method

To alleviate excess copying, my proposed method uses a linked list of segment nodes and an indexing table.

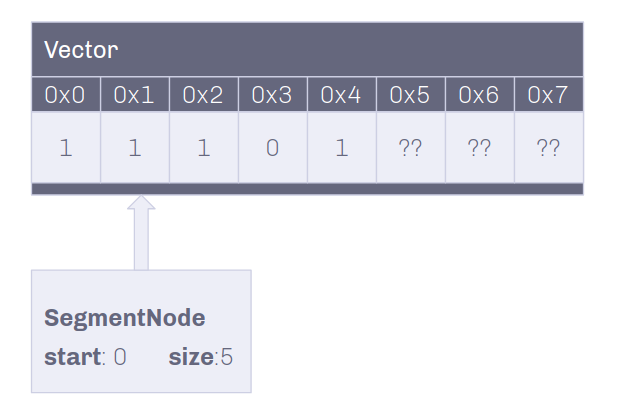

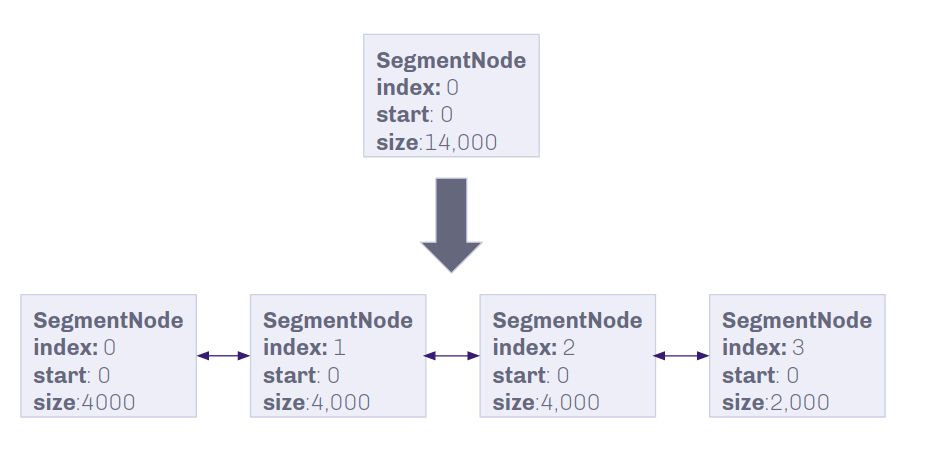

🔗 SegmentNode

The SegmentNode structure contains:

- Basic linked list node variables (previous, next)

- Shared pointer to vector of bytes

- Starting index of data

- Size of the data

🔗 SegmentList

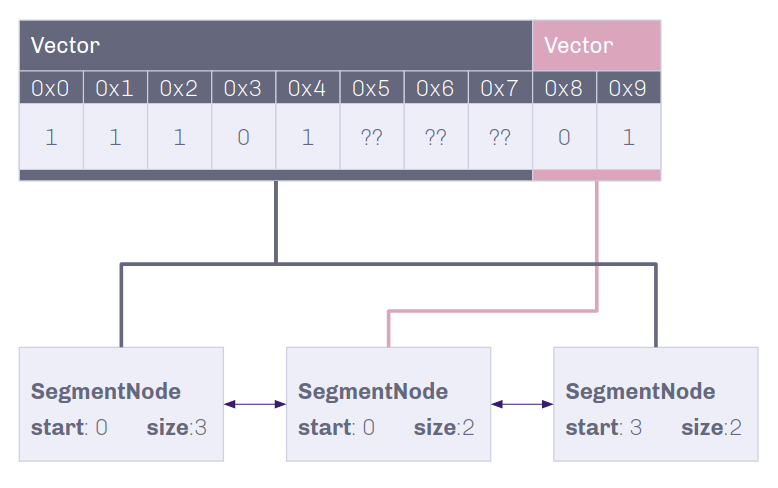

Composed of linked SegmentNodes, the SegmentList contains a linear readthrough of bytes that the gene contains.

If the data is not shared with another genome, insertion and deletion can occur directly on the genome. If not, two segments pointing towards the original data can be made, one pointing to the data before the insertion and one pointing after.

🔗 Insertion Demo on Shared Data

Insertion into non-unique data conserves as much memory as possible!

Insertion into non-unique data conserves as much memory as possible!

🔗 Largest Data Segment Size

To make insertions and deletions faster on unique data, a larger genome is broken up into segments of smaller data chunks.

Nitty (not so) Gritty on Chunk Size

With how much theory did me dirty, I decided to manually bench sizes that felt about right for the genomes without making the list too long. After using a basic linear regression on the chunk sizes and genome sizes that had the best results from my thought up many, I settled on 0.13*genomeSize. How it settled on 0.13 nicely is a mystery.🔗 Faster Access with Indexing Table

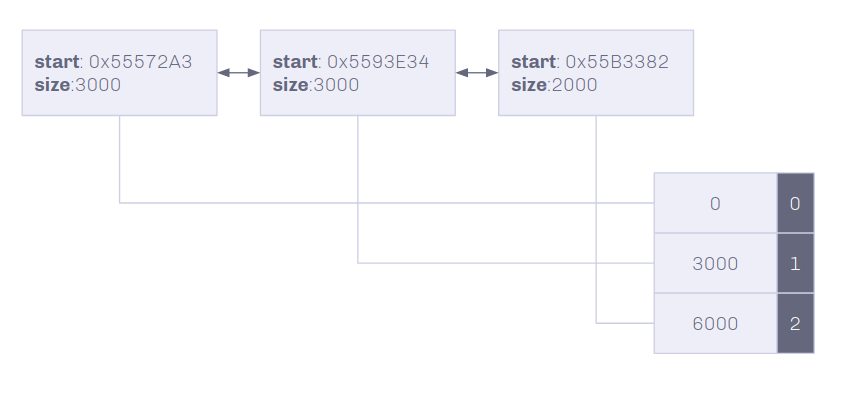

The Linked list type structure gives a simple and easily modifiable structure, but slow indexing speeds. To improve \(O(n)\), \(n\) is the number of nodes in the list, an index table with the offsets of each node into the genome will give an amortized \(O(1)\) random access to any index. Index table is a vector that contains the offset index into the genome and the node that the offset starts at.

On Insertion and deletion, the index table is truncated at the node of mutation, and is only updated within the find function. This allows for traversing the list if and only if an index past the shift mutation is needed.

🔗 Simple Find Algorithm

TableEntry SegmentList::Find(size_t index)

{

// binary search through Index Table

auto poolIndex = std::upper_bound(IndexTable.begin(), IndexTable.end(), index) - IndexTable.begin();

--poolIndex;

size_t left = IndexTable.at(poolIndex);

// iterate through segment list if not in index

while (poolIndex < Pool.size()-1)

{

if (left + Pool.at(poolIndex).size() > index)

break;

// update index table

left += Pool.at(poolIndex).size();

IndexTable.push_back(left);

++poolIndex;

}

return TableEntry(poolIndex, left);

}

Accessing a random location within the genome will give \(O(log(n))\), with \(n\) being the size of the index table, if the index is within the table. If not, accessing will cost \(O(log(n)+m)\), with m being the extra nodes needed to traverse to find the segment with the index.

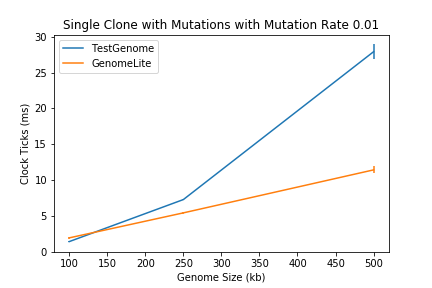

🔗 The Proposed Method that was Actually Faster

With that idea, it seemed much faster to use the splitting of nodes instead of actual data to insert into relatively large genomes (roughly 20,000 bytes and up); but benchmarks don’t lie, and after benchmarking on genomes of size 100,000, 250,000 and 500,000 bytes, the benefits were only apparent on genomes larger than 250,000.

At least it does better at some point I thought! Until an avid user of computational evolution (mentor) pointed out genomes larger than 100,000 are seldom used.

The only bright side of the benchmarks pointed at the tests of newly created genomes. In other words, smaller vector stringed together was still faster than creating a changelog.

Removing my changelog from my earlier approach, but keeping the same index table gave promising results. Surprisingly, just breaking up the vectors allowed for at least 16% faster on 75kb genomes and 26% faster on 100kb genomes.

🔗 Results

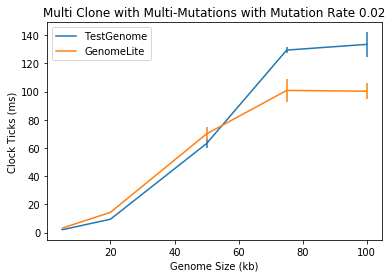

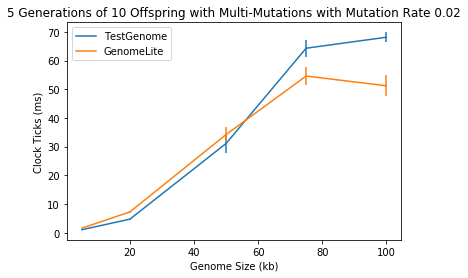

Comparing the naive approach and my current version highlights the improvements made to both memory consumption and runtime on 100 replicates of each experiment. All benchmarking is done with Catch2’s benchmarking functions.

Note: “Random” mutations are taken from a predetermined random list to fairly compare the performance of the genomes, with the mutations loop between an overwrite, insertion, and deletion.

The TestGenome is an implementation of the naive approach and GenomeLite of my simple proposed idea.

🔗 Multiple Clones with Random Mutations

This is a simulation of 0.02% insert, delete, and overwrite mutations on a 5, 20, 50, 75, and 100kb length genome, each with 100 clones.

🔗 Evolution Loop with Random Mutations

This is a simulation with the same mutations and sizes as above, each with 5 generations of 10 genomes.

🔗 Take-Aways

By trying different implementations and actually benchmarking them compared to the naive approach, the stark differences between theorized optimizations and actual optimizations were apparent; yet simply learning what does and doesn’t work in research is always a time worth spent.

The biggest takeaway from this overall finding, however, was that sometimes theorized approaches can only go so far, and when in doubt, benchmark it.

🔗 Thank You to the Team and WAVES

Though I didn’t find an incredible fast, memory saving solution, the journey through many implementations, learning many new ins and outs of c++ and optimization, and working and sharing my ideas with the team -Cliff, Jory, Tetiana, Uma, and Stephanie- and the whole of the WAVES program provided a wonderful research experience overall.