Parallelizing Your Code in C++

🔗 Parallelizing Your Code in C++

Parallel processing is something of a buzzword in software engineering. Perhaps not as much as “machine learning” or (may you forgive me for uttering the name) “blockchain”, but a buzzword nonetheless. You may someday be asked to parallelize some code as part of your job, or you may have something that you’re trying to optimize as much as possible and parallelization is the only place left to go.

The zeroth step in parallelizing code is determining whether you should. C++ is a pretty good language as far as parallelizing goes due to all of the algorithms and libraries, so the architecture is there. But not all code should be made parallel. Firstly, parallelization can theoretically only make your code at most n-times faster if you have n cpus. In practice, you can’t ever get there because of overhead.

Overhead is the amount of time and memory it takes to build the parallel architecture. Creating threads, merging threads, sending data back and forth, all of these take time, and a lot of it. If you’re summing two arrays into a third array, the point where parallelism becomes useful is often in the hundreds, if not thousands, of elements.

So when you’re looking at your code, look for large sections of redundant activity. More specifically, look for sections of code which do the same thing over and over without influencing each other. Summing the elements in an array is theoretically a more difficult problem than multiplying them all by a constant. (In practice, both of those are just a call to a c++ parallel function, but the underlying mechanics are more complex for the summation.)

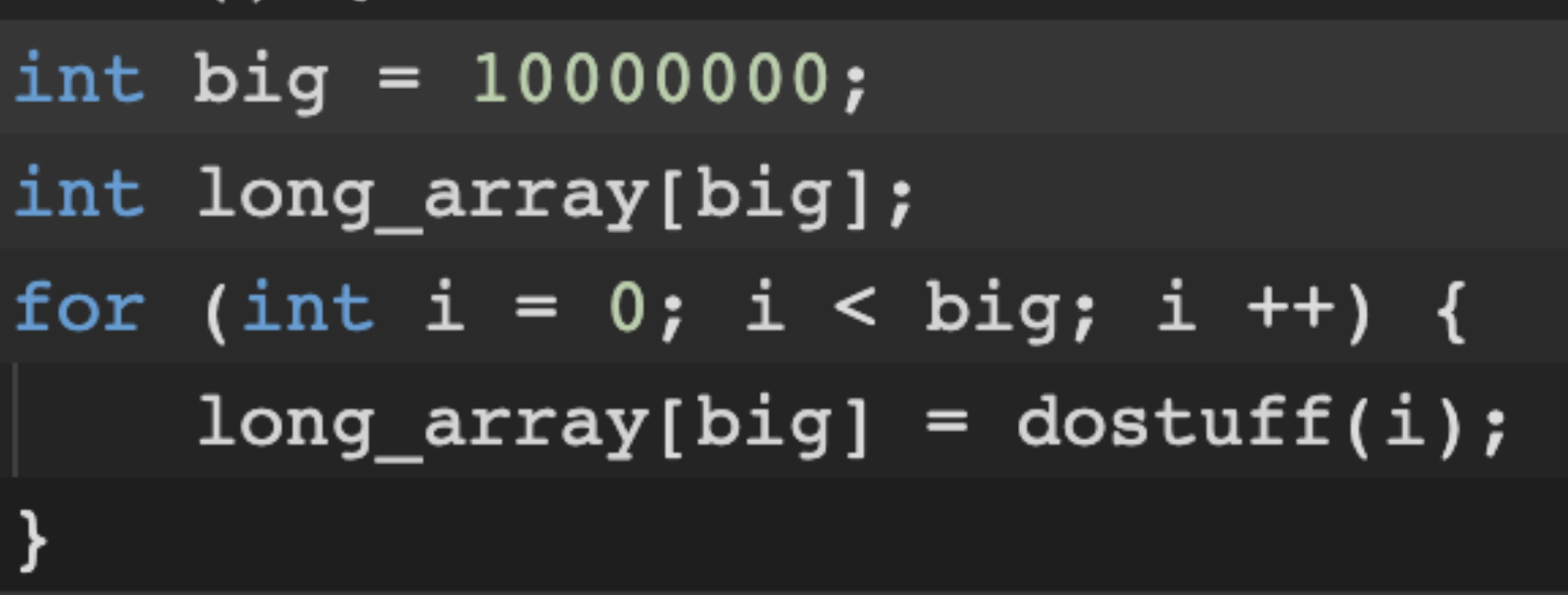

If you ever see something like this:

Then so long as dostuff is self-contained (as in doesn’t change any global variables), that for loop is perfect for parallelization. You take those 10000000 values of i, split them up among the n threads you create, and finish in (a little more than) one nth of the time. The longer dostaff takes, the closer you get to the mythical perfect linear speedup. In short, for loops like that are the perfect target of parallelism. There are more complex things we can do, of course, but let’s not worry about those yet.

The first step in parallelizing code is looking for any existing parallel algorithms. Luckily for you, there are literally hundreds of libraries, some of which are extremely good. There are the standard c++ parallel algorithms for more general use, along with some scientific linear algebra libraries and some very nice all-purpose gpu programming libraries.

So if you see something simple, like doing the same thing to every element of an array, there’s almost certainly an algorithm already made for that.

But things aren’t so simple as just using existing algorithms. Sometimes, it’s a bad idea. You almost never want to do parallelism within parallelism, so if you’ve got a parallelized for loop with OpenMP or the like, and in that for loop you do a sum over a vector, don’t parallelize that sum. You’ve parallelized the for loop, and that’s enough. More threads doesn’t mean more speedup — you can only get as many threads running at once as you have cpus to run them. Any threads past that are extra overhead, and thus slow down the code.

The second step is usually fairly simple: sending information to and from threads is expensive. So let’s limit that as much as possible. If you have sections of parallelizable code that can be put next to each other, then put them next to each other. Only return to serial code when there’s no other choice. Also, if two sections of serial code don’t refer to each other, then you can run them in parallel. It’s usually better to run serial code in parallel next to other serial code, so you don’t waste a thread which you could be using during a parallel portion, but that’s just fine-tuning.

The third step follows from the second, and it’s highly counterintuitive: inefficient code can sometimes be faster in a parallel environment. If you have code running in parallel that can go in a small number of ways (such as an if statement) based on exterior information, then it’s usually better to run the code both ways instead of calling back to the main thread. This is even more important for GPU programming, where if statements can’t be executed without stopping all other processes, and so it’s a necessity that every path be traced with the “correct” path being determined at the end.

So now, let’s have an example. Let’s consider this rather niche algorithm:

- Take m arrays of length n of doubles as an input.

- Sort these arrays.

- Add them together to form a new array

- Square each of the doubles.

- Compute all primes less than n

- Subtract each array from the squared array to get m new arrays

- Sum each new array.

- Sum the sums.

- For each new array, subtract its sum from the sum of sums. If this is odd, then add the sum of the prime indexed values to its sum. If this is even, then add the sum of the nonprime indexed values to its sum.

- Print out the m final sums in order.

- Square each array, subtract i from the ith element, and do steps 7-9 again.

- Print out the m final sums in order.

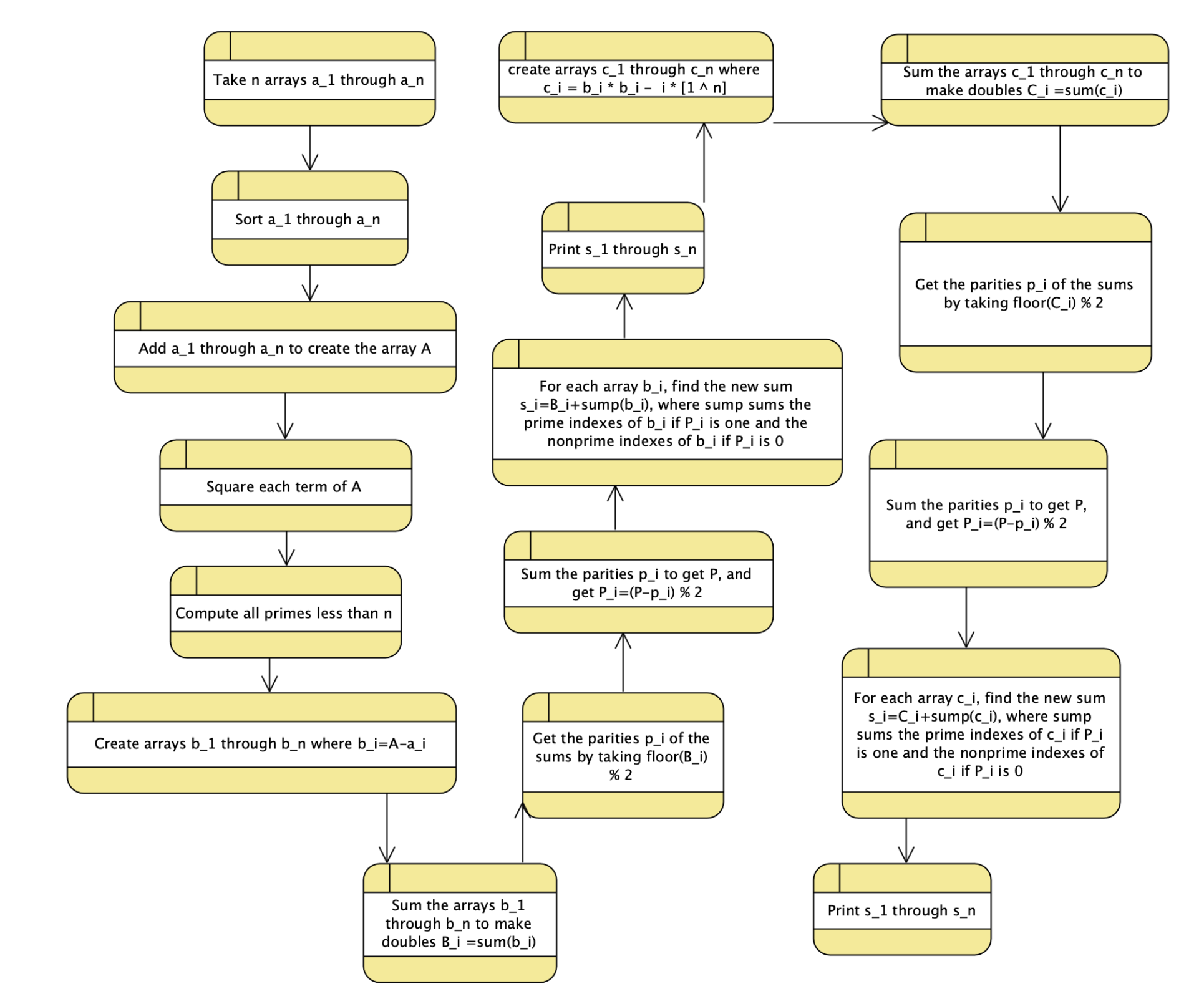

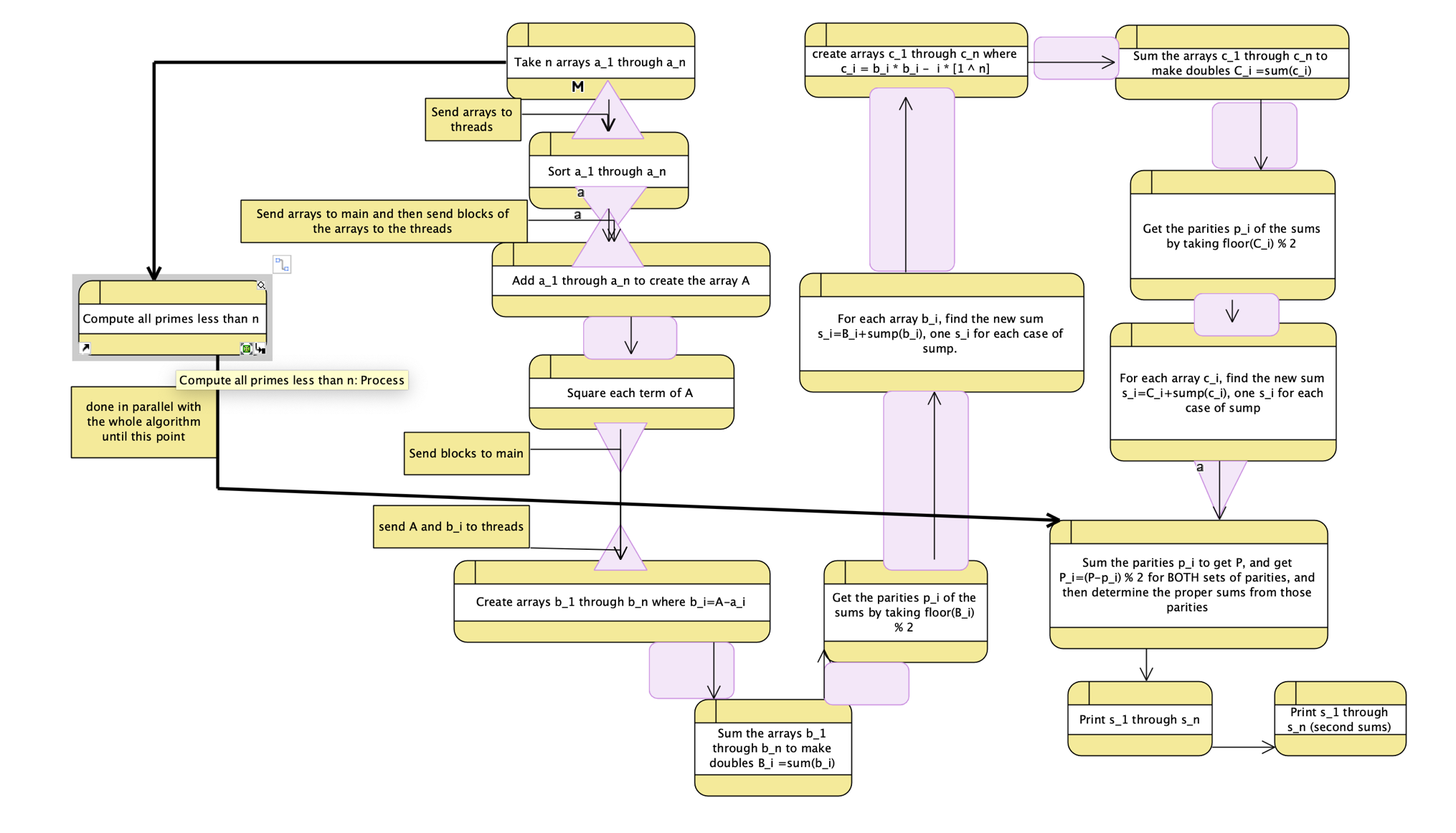

The code for this was longer than expected, so I’ll show the flow with a diagram:

Clearly, this algorithm is ripe for parallelization. First step: let’s use some c++ parallel algorithms. Sorting an array in parallel? There’s a c++ parallel algorithm for that. Doing the same thing to each element in an array? There’s an algorithm for that. Summing over an array? There’s an algorithm for that.

However, using them would be inefficient here. Why? Because it’s better to parallelize over a larger range: sorting the arrays one-per-process is better than sorting them over all the processes due to the information transfer necessary. If you have m arrays and m threads, you can do the sorting in the time it takes to sort one array. If you split the arrays up, you sort each array in the time it takes to sort one mth of an array, which is indeed faster than one mth of the time needed to sort the array, but then you have to merge it all together. And this takes time. It’s better to let arrays do their own things.

Now, let’s assume n » m. This is a pretty valid assumption in most circumstances. This means it’s far more practical to send all of the arrays to the main process for summation than any of the alternatives, although we can still do a parallelized for loop for the actual sum, taking a block of each array and passing it to a process.

The squaring of this new array’s elements, though? We can do that with a c++ algorithm, no problem.

For everything else, the c++ algorithms aren’t particularly useful. Remember that parallelizing code in a parallelized section is rarely a good idea. The overhead is just too much.

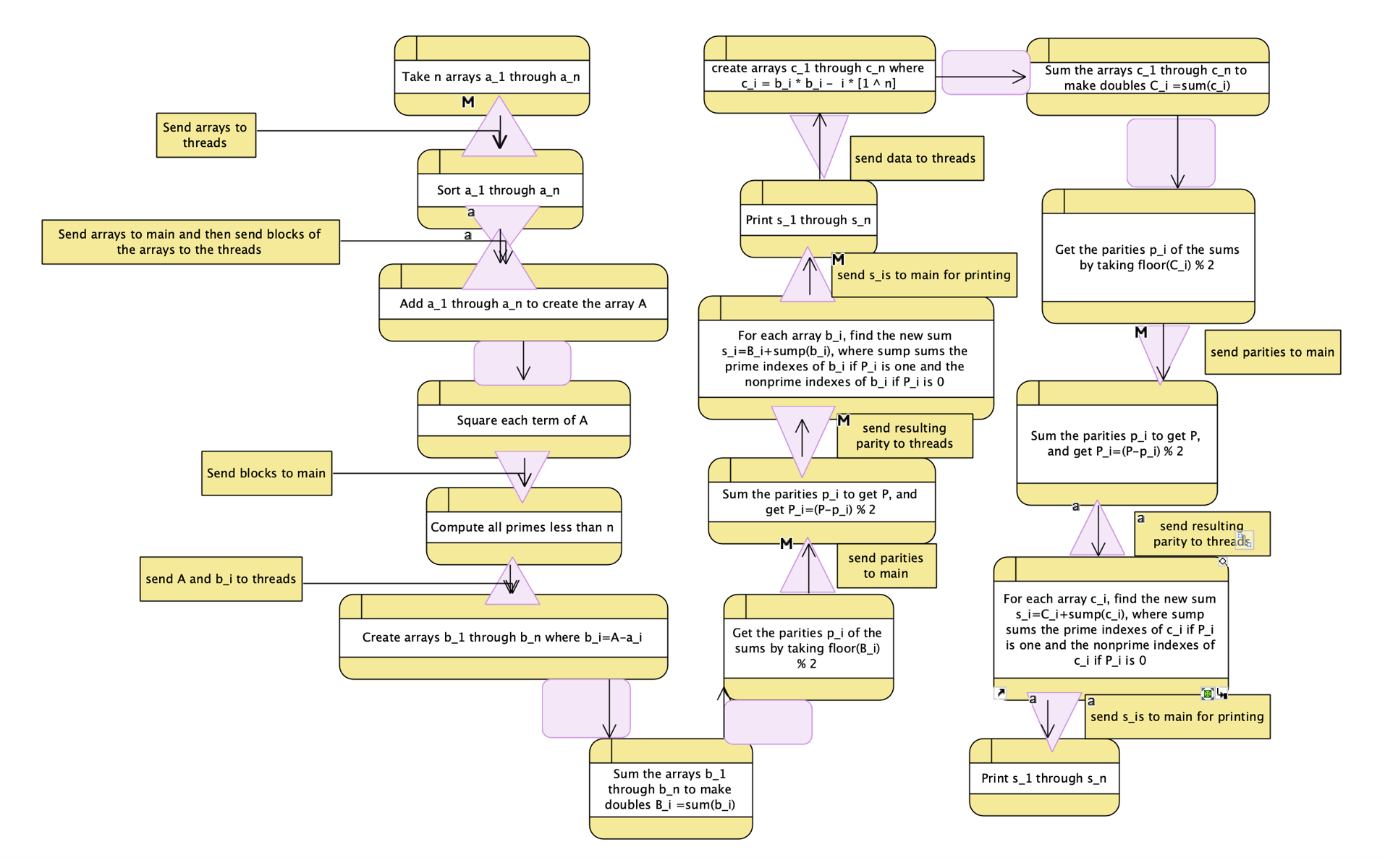

So what do we have now? Our current structure is (where the purple triangles show a move to or from parallelism, with the wide end being parallelized):

There’s a problem here, though: with the current structure, we have to return to serial a LOT. We can do the summing over arrays in parallel, but we have to return to the serial every time we check whether the sum of other sums is even or odd.

So let’s fix this by moving parallel sections together.

The printing can happen at the end, and we can do all the summing, squaring, and subtracting of i in parallel, only returning to main to check even/odd.

As for generating primes, that already happens during a serial process, but it seems..odd to have it there. Let’s make it happen as a serial block in parallel: give it a thread during the sorting of the arrays.

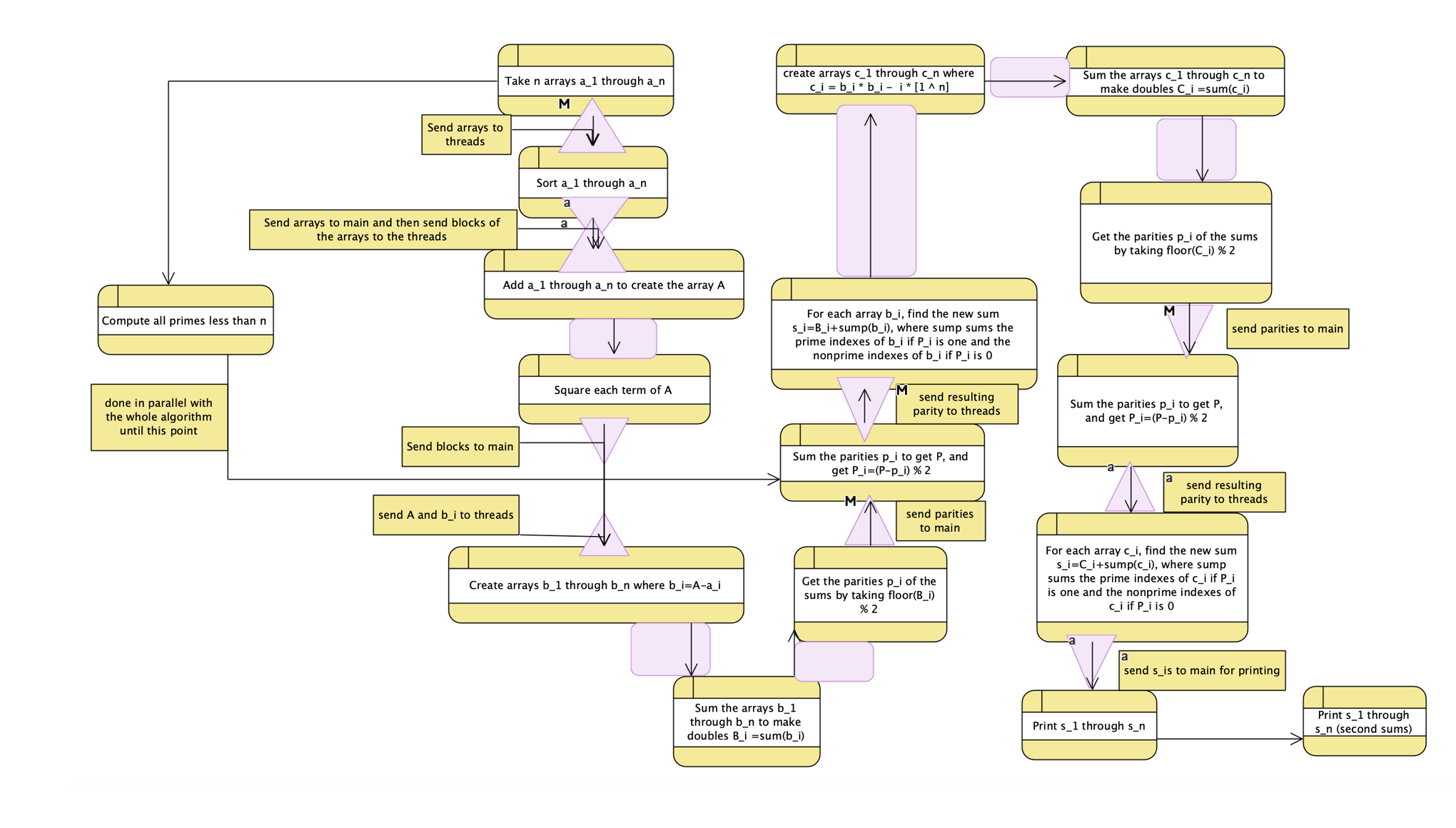

Now we have:

There’s no particular way to get around the need to return to serial to get the sorted arrays from the threads, and so we’ll need to send them out again. But we can improve the even/odd comparison. What if we didn’t have to return to main at all? Until the end?

We do this by handling all options. We compute all four sums for all four cases, and return that to main. We then check, in-main, which ones we should use. Then we print them out, and we’re done. This gives us a pure parallel section before the final checking and printing.

And now we’re done. That was parallelizing your algorithm 101.

🔗 Comments? Questions?

Jump on the twitter thread below to chat!! ☎️ ☎️ ☎️

Jamie Schmidt wrote an example-driven primer to #parallelizing #cpp code (complete w/ the biggest flow chart you ever did see)https://t.co/q2A7SxRm5k

— Matthew A Moreno (@MorenoMatthewA) June 15, 2020